Spring nearly always brings the first blooms of optimism for the housing market. Homes certainly sell in the winter months. Builders take out permits and start construction on new homes all 12 months of the year. These truths notwithstanding, the combination of the holidays and lousy weather sap the enthusiasm for home shopping for most people. As the weather warms, homeowners looking to move emerge like hibernating bears and begin to shop.

This spring that warming is especially relevant to real estate and homebuilding professionals. The last half of 2018 was not a particularly good time for the housing market and the tepid conditions carried into the first weeks of 2019. The conditions weren’t like 2008, or even 2013, but the housing market slowed for the first time since the Great Recession.

Rising interest rates – or rather the perception of rising rates – and rising home prices were the main culprits in the 2018 slowdown. The specter of the Great Recession, and the mortgage crisis that precipitated it, loomed over the housing market. Perhaps more than the actual impact of rising rates and higher prices, the memory of the fears of 2008-2009 kept interested buyers – particularly first-time buyers – out of the market in the latter half of 2018. As March faded into April, there were signs that facts have overcome fear, and the housing market is making a rebound.

Fear Factors

The much-chronicled housing bubble and mortgage crisis of the 2000s did throw the housing market in the U.S. for a loop. The short version of the housing crisis is this: artificial demand and overextended mortgage credit inflated new construction and the value of homes to the point that a period of retraction was necessary to balance the market. The severity of the imbalance meant that the duration of the correction was unusually long. Because the conditions that caused the great imbalance in the markets didn’t exist in Pittsburgh, the correction was virtually nonexistent in Pittsburgh. While home values plummeted around the country, most neighborhoods in Pittsburgh saw little, if any, depreciation from 2008 to 2009.

What the housing crisis wrought – and this includes Pittsburgh – was an emotional scar on the collective psyche of the American homeowner. Around eight million families lost their homes to foreclosure because of the mortgage crisis and recession that followed it. Almost everyone in America was related to or knew someone who was affected by foreclosure and those memories linger today. This is especially true for younger adults. The majority of the so-called Millennial generation were coming of age or young adults in 2008. For them, the certainty of the investment value of the single-family home doesn’t exist.

Over the past five or six years, as the share of Millennials who have become home buyers has lagged previous generations, we’ve learned that this uncertainty about home ownership has made renting more attractive to Millennials than to their predecessors.

This uncertainty was a factor in cooling off demand in 2018. Realtors in Pittsburgh had seen a rising share of Millennial buyers each year going back to 2015 – reaching as high as 45 percent of the mortgages originate by Hanna Financial Services in 2017 – but that trend stopped in 2018.

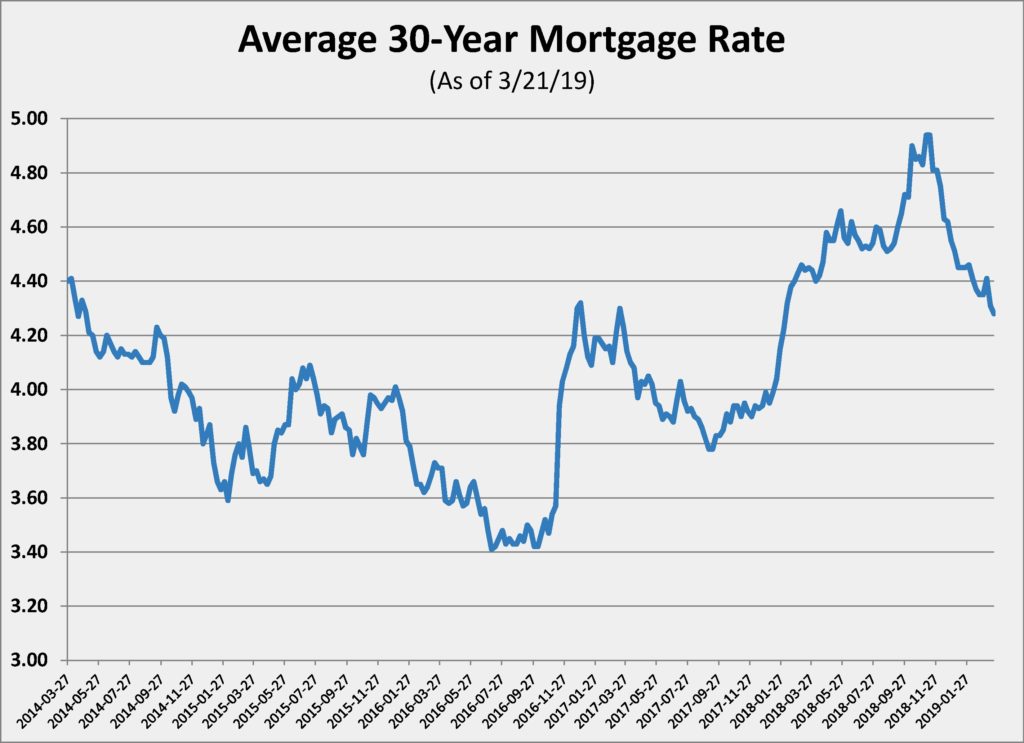

Millennial mistrust was only one factor in the cooling off in 2018. The Federal Reserve Bank raised its overnight Fed Funds lending rate four times during 2018, fueling fears that borrowing costs were going much higher. The reality of the interest rate trend is that, while short-term interest rates have climbed by two percent since late 2015, the 30-year mortgage rate was essentially the same at the end of 2018 as it was at the end of 2013, and nearly two points lower than the peak of the housing bubble in 2007. For a few days in the early fall of 2018, 30-year mortgage rates broke through the five percent barrier, but that spike faded within one week. At the beginning of March 2019, the interest rate and points for an average 30-year borrower was 4.8 percent.

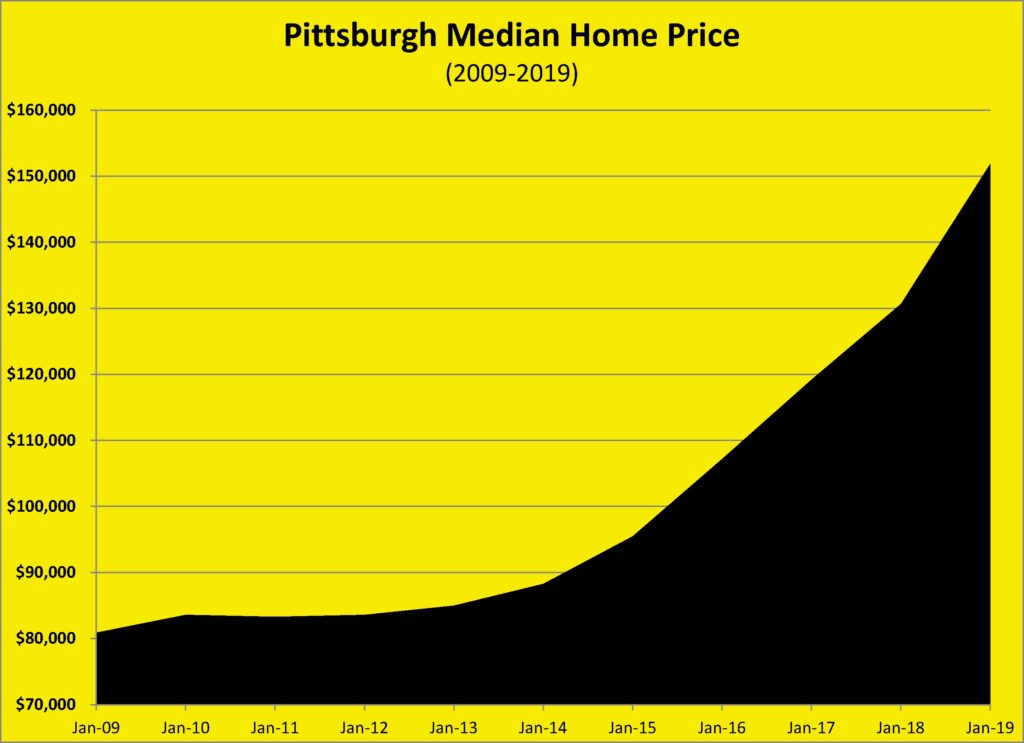

Another factor chilling the housing market was the high price of homes. This too was at least partly perception instead of reality. For buyers living in hot gateway cities, like San Francisco, New York or Washington DC, prices have indeed reached stunning highs. In those, and other major cities with high population growth, home costs exceed $500 per square foot, a level which precludes the majority of the population from owning. Those extremes aside, however, the price of most homes have simply appreciated back to the levels that homes would cost had the Great Recession not occurred. Home prices have been growing at five percent or more for five or six years, but that accelerated appreciation was a reaction to the depreciation that came between 2009 and 2011. In other words, in most American towns the price of a home in 2018 was the same as if the housing boom and bust of the 2000s never occurred, and normal modest appreciation nudged prices higher every year. Prices were certainly higher for first-time buyers, but existing homeowners would have received the same appreciation benefit on the home they were selling.

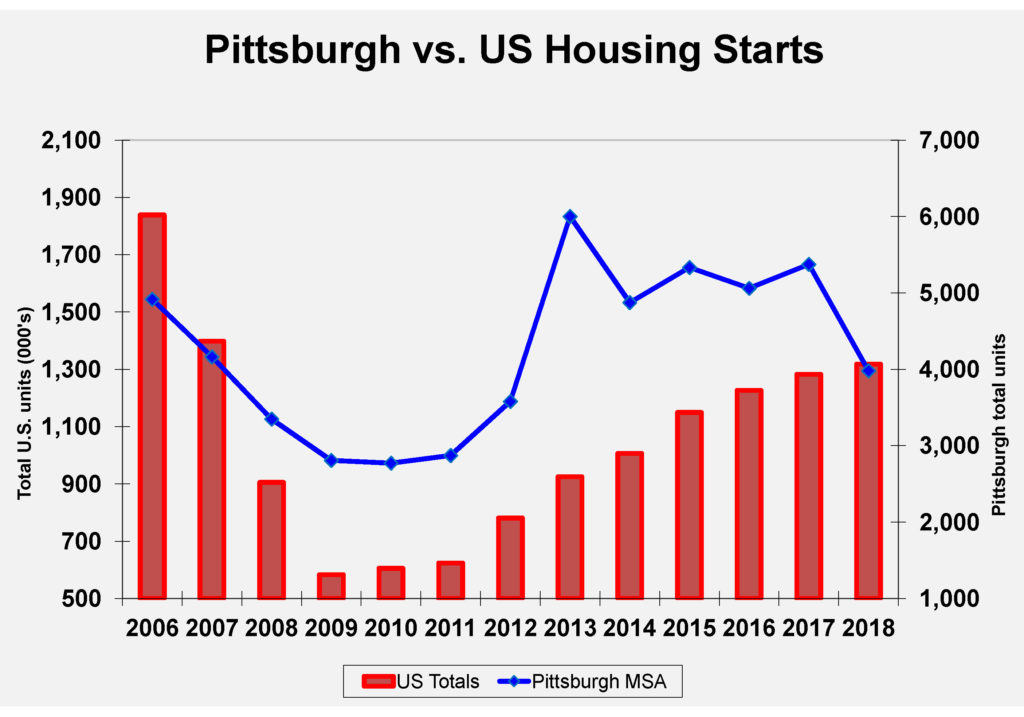

One factor that was real in 2018 was tight supply. As has been true for the decade since the Great Recession, fewer homes have been for sale in the U.S. each year than in the average year prior to the downturn. And new construction has been much slower. Even a decade removed from the housing crisis, construction of new single-family homes in 2018 was muted. The 863,000 new homes built last year was the highest since 2007, but that total was lower than every year prior to 2007 except 1991. Low inventory of existing homes should be a boon to new construction; however, even though the number of homes for sale remained low, development of new lots also slowed. This meant that homebuilders had fewer options and more incentive to raise prices.

“I think it’s lot driven,” says Paul Scarmazzi, CEO of Scarmazzi Homes of Canonsburg. “Nationally, we’re not producing enough new construction that it affects affordability. When you lose density [in development] it becomes more expensive to build. On the West Coast there are markets where the land costs are more than 50 percent of the price of the home.”

“The new construction challenge is cost. There is a great discrepancy between new home price and resale price,” says Tom Hosack President/CEO of Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices. “That’s driven the tariffs on lumber, the lack of labor, the cost and shortage of lots, and environmental costs. It is so expensive to develop these days.

“It’s tough for small custom builders to get loans for spec homes. We are seeing now more cases of custom builders buying a house on five acres, tearing the house down and building four or five homes that are in the $350,000 to $400,000 price range. That’s more affordable.”

This stew of fears and tight supply made some buyers defer the decision to buy in 2018. The housing market has been recovering steadily since 2011, so a six-month slowdown in that recovery should not be cause for alarm. Cooler conditions in 2018 caused most economists to predict cooler conditions in 2019, but the forecast is for normal appreciation and normal home sales. The first signs of spring are bringing evidence that normal housing market conditions have returned.

Turning the Page on 2018

If it seems a bit unusual to be talking about homeowners’ emotions instead of data, it’s probably because the economic data that signals how the housing market is doing is better than the market is performing. As you might expect, the housing market – whether it’s existing home sales or new construction you’re talking about – likes a strong economy. And coming into 2019, the U.S. economy was strong.

Probably no economic metric leads the housing market so reliably as employment. Check the statistics on unemployment and home sales or home construction. Sales and construction rise as unemployment declines, and vice versa. Unemployment in the U.S. is lower now than in generations, falling to 3.8 percent in February. By that measure, the housing market in Pittsburgh and the U.S. overall should be at record high levels, but that’s not the case. Likewise, the movement of interest rates directly bears upon the housing market, which is driven by mortgages. Interest rates have been historically low for a decade, without a significant impact on the recovery of the market. Perhaps the only time-tested metric that could predict that the housing market would not snap back from the Great Recession was wage growth, which was below the rate of inflation until mid-2017. Even with wage growth as a driver, the response has been counterintuitive. The tight labor market has pushed wage growth up to three percent for most of the past 18 months. Yet, during that time, sales and construction have been largely flat.

Recent stability in two key areas is the source of confidence that the housing market will put the fears of late 2018 in the rear view mirror. The Federal Reserve Bank’s minutes from its February Open Markets Committee meeting indicated that the central bank was seeing fewer reasons to raise its Fed Funds rate in the near future. While this had no effect on long-term rates, which were already back down well below five percent, the Fed’s growing patience with interest rates has had a soothing effect on buyers. Real estate agents and builders report that traffic was much higher in March.

“At the microeconomic level, Pittsburgh’s housing market is marked by the same issues as the national market, but to a greater extent. “

Construction material costs have also moderated. Price increases in steel and lumber have reversed. Fuel costs, which have a ripple effect on many building products, have also pulled back. The tight labor supply will still push the cost of labor higher, but the overall construction inflation curve has flattened or even fallen slightly.

For these and other reasons, most economists and housing market associations see room for modest growth for the housing market in 2019.

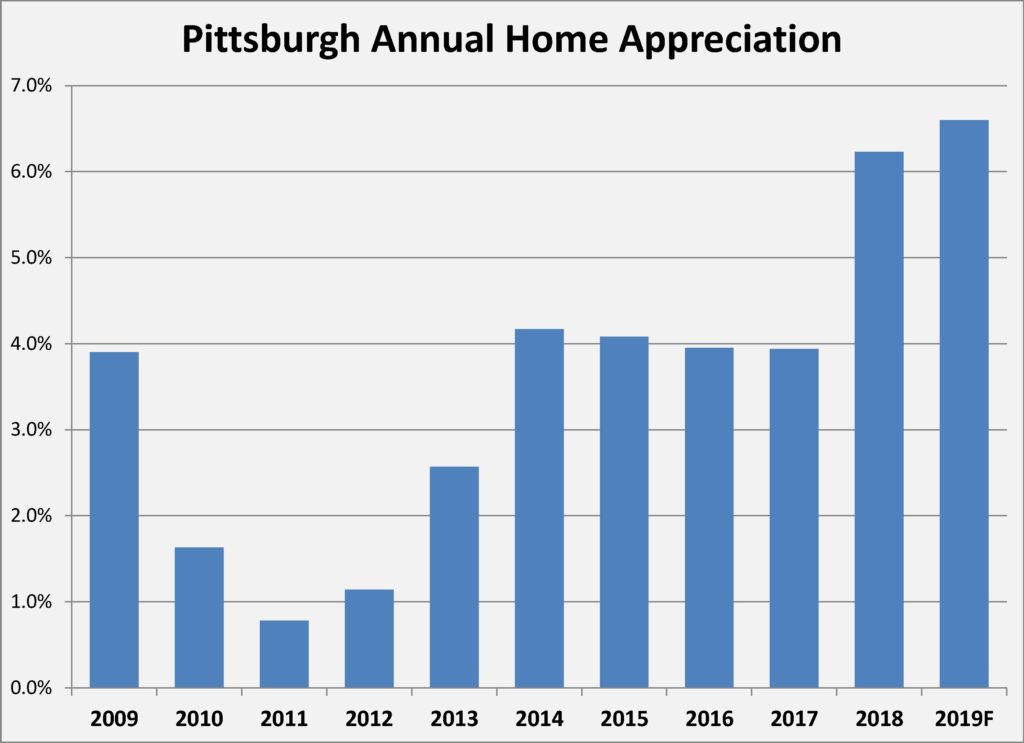

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) seems to be assuming that some of the funk that beset the market in 2018 will continue into 2019, as it forecasts that appreciation in home values will increase by 2.2 percent this year. The Realtors are more bullish on new construction, expecting an eight percent jump in housing starts in 2019.

By the same token, the association that represents builders, the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) is predicting that housing starts will increase by only 2.5 percent. NAHB is even more bearish on home sales, predicting that existing home sales will decline 1.3 percent in 2019 and 2020, with sales of new homes increasing 1.1 percent and 1.7 percent respectively. Those are hardly robust forecasts.

At the microeconomic level, Pittsburgh’s housing market is marked by the same issues as the national market, but to a greater extent.

More than any other factor, the Pittsburgh housing market has been influenced by the lack of inventory, both for existing homes and new construction lots. Zillow reports that the inventory of homes, new or existing, fell 11.9 percent in 2018. Reports from West Penn Multi-List and ReMax confirm this trend, noting that softer year-end sales boosted the inventory slightly from a three-month’s supply to nearly four-month’s supply. Nevertheless, the average days on market were just over 60 days in Pittsburgh. New construction was only slightly helpful, as new single-family detached home starts increased by 222 homes in 2018. That gain was offset by a decline of 243 units of townhome construction.

“The whole market is locked up because the people who should be moving up to new construction don’t have that opportunity so they are staying put. That causes the inventory of resale homes to be lower than it might be,” explains Hosack.

These dynamics explain why Zillow saw the median home price jump 7.6 percent to $151,900 in Pittsburgh last year. The real estate service company forecasts that home prices will appreciate 6.6 percent in 2019 in Pittsburgh. That’s almost triple the consensus forecast for appreciation nationwide. NAR’s outlook for Pittsburgh’s home prices is more conservative, at 2.6 percent, but almost 25 percent higher than its U.S. forecast.

Local real estate professionals and home builders paint a picture that suggests that above-average appreciation will continue the trend. As warm weather approaches, the inventory of existing homes for sale has grown, but not dramatically so. New construction remains constrained by limited development and fewer existing lots than the market needs.

The year is still young, and the prime buying season is just about to begin, but the data from the first two months confirms the cautious optimism of the professionals. According to West Penn Multi-List Inc., transactions and listings are up, while prices have remained firm. Some of the highlights from January and February sales are:

Closed sales are up 4.57 percent (3,275 units in 2019 versus 3,132 in 2018);

Closed sales volume is up 3.70 percent ($583,539,500 in 2019 versus $562,691,988 in 2018);

Average sale price is down 0.82 percent ($178,180 in 2019 versus $179,659 in 2018); and

Home listings are up 4.24 percent (5,069 units in 2019 versus 4,863 in 2018).

“If you talk to any agent now, they are busy,” says George Hackett, current president of West Penn Multi-List and president of Coldwell Banker Real Estate Services, Pittsburgh. “January and February were pretty normal but traffic really took off in March. My children are in the mortgage and title businesses and they say they are swamped.”

Demographics are playing a factor in Pittsburgh’s housing market, and in a confusing way. As has been noted endlessly, the share of Pittsburghers over the age of 65 is higher than in almost any other city in the U.S.; yet the inventory of senior lifestyle housing is lower than in most cities. That has a ripple effect, as empty-nesters have fewer options for leaving their family home, which means there are fewer family homes for younger people to buy.

“The empty-nester market is absolutely still strong, but with that comes competition,” notes Scarmazzi, whose Epcon-based communities are now competing with production builders from outside Pittsburgh. “We think we know that empty-nester lifestyle market really well, but we’re investing to make sure that’s true.”

Pittsburgh is also getting much younger at the same time it is aging. (Here comes the confusing part.) The median age of a City of Pittsburgh resident has fallen below 33 years old, while the median age of an American is 44 and the median age of an Allegheny County resident is nearly 46 years old. There is a rush of new people moving into the region. They are younger and want to live in the city proper, but the supply of houses is very limited in the city and more difficult to develop.

What all this means to the housing market is that, while Pittsburgh’s population is declining for natural reasons (more people dying than being born), there is growing demand for two very different types of housing that outstrips the supply. This trend will support higher prices for homes until fewer people move to the city or new construction returns to the pre-recession levels of 3,500 or so single-family homes each year. Tom Hosack sees evidence that more density in popular suburban communities would relieve some of the market pressure but concedes that municipal zoning restrictions aren’t likely to change.

“Everywhere in the North Hills they build a townhome community they sell out. It’s the most affordable property. The challenge is there is so little zoning that accepts multi-family in this market. Pine Township and Cranberry Township have no appetite to have any more of that than is already there.”

The upside of this tight supply/high demand market is that homeowners can be confident that their mortgage payments are building equity and wealth. That’s how the American dream of home ownership is supposed to work. And for those trying to buy into that dream, the strong Pittsburgh economy that is attracting young people is also pushing salaries higher. That should make the leap from renting to buying less painful.

For younger Western Pennsylvanians, the pain is considerably less than that of buyers in other cities. Even though price appreciation is solid in Pittsburgh, the region is still relatively affordable. As a metropolitan area, Pittsburgh consistently ranks high in affordability for first-time buyers. As an example, a report by Redfin found Pittsburgh to be the second-most affordable city in the U.S. Studying the prices of the homes for sale during 2017 and 2018, Redfin calculated the number of homes available that could be purchased with a mortgage that consumed 30 percent of the median Millennial’s household income. (In Pittsburgh, that’s $70,169.) Using those criteria, 87.5 percent of the homes listed during the past two years were affordable for Millennial buyers. Only St. Louis ranked higher.

One other mitigating factor in Pittsburgh’s housing market is the relatively low level of distressed homes relative to mortgage repayment. RealtyTrac, a South Side Pittsburgh real estate information service, reported that there were 1,660 homes categorized as distressed by lenders at the end of 2018. That’s right at one percent of all Pittsburgh homes. Even that number is a bit misleading, as 47 percent of those categorized as distressed were only behind in payments and had not entered the foreclosure process. Buyers looking to get a deal by cherry picking a foreclosed home will have a hard time finding one in Pittsburgh. It’s still a seller’s market.

“If you price the home right you’ll have it sold quickly. There are a lot of sellers that won’t even accept contingency offers now because there are so many people looking that they don’t have to,” says Hackett. “With the rates coming down, plenty buyers out there and multiple offers in many cases, if people don’t put their homes on the market now, they aren’t serious about selling.”

What do all these technical economic factors mean for Pittsburgh’s housing market in 2019? As much as anything else, the conditions in Pittsburgh mean investing in a home is safe. It may be more difficult to find the home you want in Pittsburgh now compared to 20 years ago, but a buyer can feel confident that the home they choose will hold its value, even if they must pay a little more for it. Compare that to the stories of home buying in San Francisco or New York (or even Philadelphia), where “house poor” is the norm. Homes in Pittsburgh are still affordable and, although no longer cheap, are becoming more valuable.

“Interest rates remain favorable. We’re not seeing the kinds of things we saw happen in 2006 and 2007, when you had ‘no-doc’ loans and mortgage brokers driving the market. Fundamentally, we’re in balance,” concludes Scarmazzi. “I think we’re looking at a good market for housing this year and for the foreseeable future.” mg