It is the Pittsburgh region’s biggest construction project. Coming on the heels of the Shell cracker, the Pittsburgh International Airport Terminal Modernization Program (TMP) ensures that the region will have had a billion-dollar project underway for nearly a decade. It is also a project that defied the rollercoaster ride of a global pandemic and a post-pandemic inflation spike.

Pittsburgh’s TMP is somewhat unique among major public construction investments in that it is being undertaken with the intention that the project will primarily benefit the users of the airport, rather than having a multiplying economic impact. For that reason, the construction costs are being borne by the airport’s users instead of the county’s taxpayers. That does not mean that the project is without its detractors, mostly those who ask why the project needs to be done in the first place.

Commercial air travel is relatively new in terms of human activity. The equipment and facilities used to operate airlines and airports are still evolving. The new terminal will effectively replace the current 31-year-old Pittsburgh International Airport, which replaced the Greater Pittsburgh International Airport only 40 years after it opened in Moon Township in 1952.

When it opens in March 2025, the new terminal will change the experience of traveling to and from Pittsburgh by air. There will be triple the amount of covered parking. The security checkpoint will be twice as large. The designers estimate that the time needed to go from curbside to airside will be cut in half. That is a major improvement in function, and the new airport’s design is meant to improve its form too.

The modernization is intended to give Pittsburgh the airport it deserves, in the words of Christina Cassotis, CEO of the Allegheny County Airport Authority (ACAA). While it is being built, the modernization program is giving the construction industry in Pittsburgh a boost it needs.

Understanding the Need

Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) opened in October 1992 to industry acclaim as an airport of the future. Built at a cost of $800 million, PIT was the first in the world built as a connecting complex, with a pre-security landside terminal and an X-shaped airside terminal with four concourses. Its design was lauded in the travel industry for its efficiency, especially for the reduced idling distances that planes were required to traverse, an improvement that saved the airlines $12 million annually in fuel costs alone. PIT also pioneered the modern air mall, with a groundbreaking agreement with retailers to price merchandise at levels that matched their other locations outside airports.

But PIT also opened a few years ahead of disruptive change in the airline industry. The airport was built as a hub for U.S. Airways, which was beginning to experience financial pressures. Less than nine years after PIT opened, terrorists highjacked commercial domestic flights to attack Manhattan and Washington DC on September 11, 2001. Three years later, U.S. Airway abandoned PIT as a hub.

The move by U.S. Airways reduced the number of daily flights by 250. PIT became underutilized and remained so for most of the next 20 years. When the ACAA hired Christina Cassotis as CEO in 2015, her charge was to rebuild origination and destination (O&D) traffic from the ground up. Today, there are 61 non-stop O&D flights daily, almost double the 36 daily non-stop flights in fall 2015. But that additional traffic, while impressive, cannot generate the kind of utilization that an airline hub of the 1990s would create.

Jonathan Potts, vice president of communications for the ACAA Terminal Modernization Program, points out that while fewer flights may have resulted in fewer passengers overall, the change in the type of flights has also created an imbalance in how the two terminals are used.

“Bear in mind that we are only replacing the landside terminal – where you check in, go through security, and pick up your bags – and not the airside terminal,” says Potts. “Here’s why: When Pittsburgh International Airport opened in 1992, we were a U.S. Airways hub, and the airport was built to U.S. Airway’s specifications. Back then, 80 percent of our passengers were connecting passengers, so they never set foot in the landside terminal. They landed in the airside terminal, got off their plane, and then got on another plane to fly to their final destination.

“U.S. Airways went through two bankruptcies, de-hubbed PIT, and was swallowed in a merger with American Airlines. Today, PIT is an origin-and-destination airport. So, 95 percent of our passengers begin and/or end their trip in Pittsburgh. That means there are many more people using the landside terminal today than there were when we opened 31 years ago. It is inadequate for our passengers’ needs, and many of the systems and equipment are aging out and prone to breakdown.”

Moreover, one of PIT’s more popular assets, the massive 12,000-acre footprint and sprawling facilities that kept passengers from being overcrowded and bottlenecked, became a liability. Passengers must travel longer distances and manage an inefficient post-9/11 security process that is less convenient than in airports designed or updated since 2001. The large amount of unused or underutilized space also means that ACAA spends much more on maintenance and cleaning than it would on facilities that were right-sized.

Cassotis has advocated for an airport that matched the reality of air travel in Pittsburgh in the 2020s and 2030s. She detailed the major issues that ACAA faces operating a 1980s-designed airport in a recent editorial in the Pittsburgh Business Times.

“The landside terminal, where you check in, go through security, and drop off and pick up baggage, needs to change. It was built before TSA existed and for an airline that no longer exists,” Cassotis wrote. “We have an outdated baggage system that includes a lengthy eight miles of baggage belt. We have an international arrivals process that is badly in need of redesign. We have conveyances, like escalators and elevators, in a four-story building that are 30 years old and in need of replacement, and trains that cost millions annually to maintain. Functionally it no longer makes sense”

Defining the Solution

In June 2018, ACAA selected Jacobs and Paslay Group from Irving, TX as program managers for the terminal modernization. One month later a design team was selected, led by a joint venture of Gensler and HDR, in association with Spanish architect Luis Vidal + Architects. Michael Baker International, which has served the ACAA for 30 years, is also providing engineering and architectural services for the Multi-Modal Complex (MMC). The team includes dozens of professional firms as subconsultants. It was the ACAA board’s and Cassotis’ directive that the architects create a design that reflected the values and characteristics that are unique to Pittsburgh. The result was a concept they called, NaTeCo, an acronym for nature, technology, and community.

“It was important to the airport authority to design a place that was uniquely of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh International is an origination and destination airport, so the first impression people get of the city and the region is often the airport,” explains Carolyn Sponza, studio director and principal with Gensler. “The NaTeCo concept pulls out three of the major drivers of what we think is important to Pittsburgh and tries to infuse those in the architectural character of the airport.”

Sponza lays out how each of the three parts of the concept is represented in the final design.

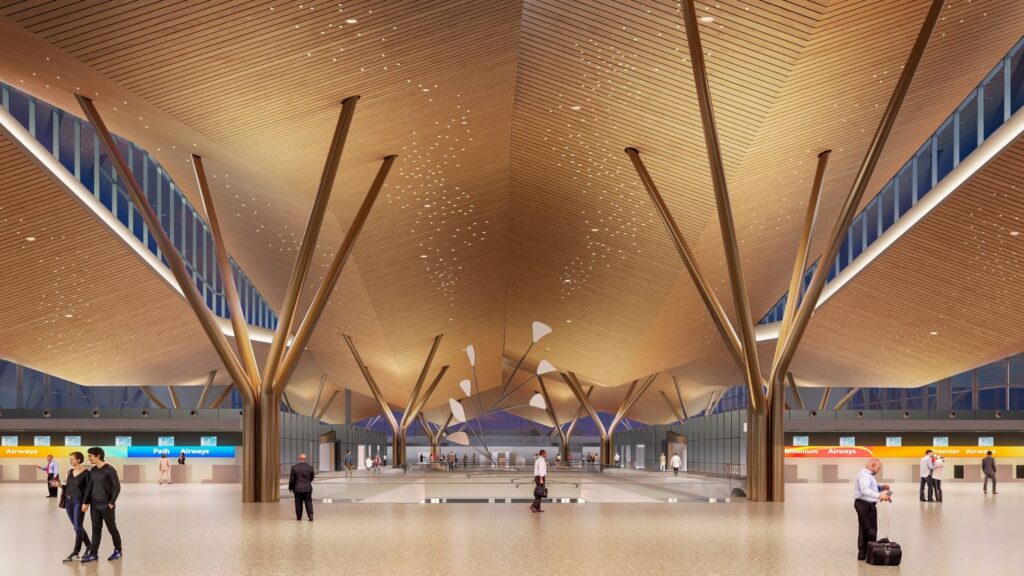

“We wanted passengers to have the benefit of exposure to nature and the positive biophilic relaxation qualities of being in nature while they were in the airport. Western Pennsylvania has the change of seasons, all the lush landscape, and the tree covered hills,” she says. “Some of the natural features we’ve integrated into the airport are a series of outdoor terraces that speak to three of the microclimates or natural regions of Western Pennsylvania. In the architecture itself there are natural features. The form of the roof replicates the rolling hills of Western Pennsylvania. Also, the tree-shaped columns are a signature structural support on the upper level of the building. There are also little details in the design such as leaves that are indigenous to Western Pennsylvania embedded around the base of those tree columns.”

Sponza says that the design team focused on using technology in a way that mimicked Pittsburgh’s leadership in emerging technologies, using smart technologies that helps to guide passengers and make the experience of traveling to Pittsburgh more intuitive and less stressful. She explains that for the third concept, community, the design team examined how PIT was currently being used to bring the community into the airport.

“One of the things we did when we started was to audit all the things that the airport was already doing. It’s only because you have a great space that is multifunctional that you can have different people come in and do different programming from the community,” she says. “We wanted to make sure there was space for all those activities in the new plan, both on the outdoor terraces and inside. We really thought about how the community be welcomed in and use the space.”

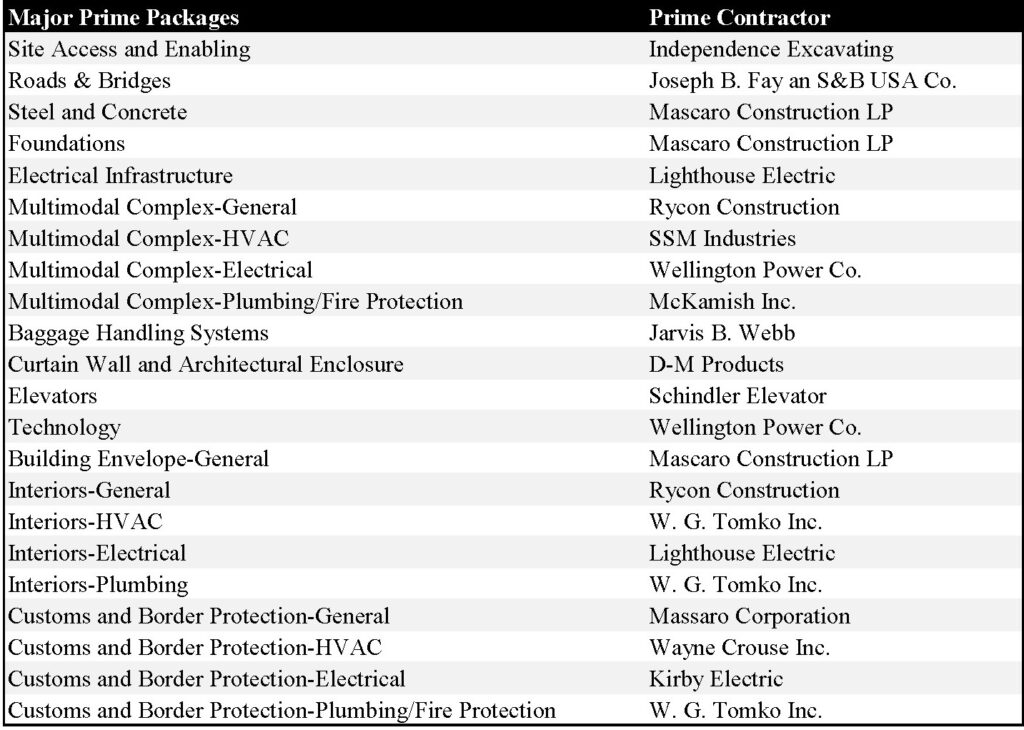

The design concept was revealed in early 2019. In April of that year, the construction management team was selected. Construction management for the TMP is split. The team of PJ Dick/Hunt is the construction manager for the new terminal and existing terminal renovations. Turner Construction is the construction manager for the Multi-Modal Complex, including the new parking garage.

The new terminal is 700,000 square feet and combines the airside and landside functions that were separated in the 1992 design. The TMP also includes the 1.42 million square foot Multi-Modal Complex that will house the rental car facilities, with space for 1,000 rental cars, and a 3,300-car parking garage available for passengers and the public. At the time it was approved, the TMP was to cost $1.2 billion. That budget has since been increased to $1.57 billion, as time and extraordinary circumstances have dictated.

“In terms of the cost, we are not using local or state tax dollars, though we are receiving some federal infrastructure funds – about $23.5 million in federal dollars,” says Potts. “Most of the $1.57 billion for the project comes from long-term bonds that will be repaid from airport operating funds. We do not operate with tax dollars. Our revenues come from fees paid by the airlines that fly out of PIT, parking, concessions, and other miscellaneous fees.”

Potts notes that the operating costs for the airport will be positively impacted by the reduction in size and improved efficiency. In 2023 dollars, ACAA will save $18 million annually at the current levels of flights and services.

One of the major risks of a project of this size is its timing. Planning for the TMP began five years before the professional team was assembled. During the airport’s design, Shell Chemicals was building its $7 billion polymers plant in Monaca. Airport leadership was wary of the risk of budget creep over such an extended period and determined that the project would be most successful if it attracted Pittsburgh’s best contractors. Paul Hoback, executive vice president and chief development officer for ACAA, notes that there were decisions made during planning that were intended to optimize the market’s attention on the TMP.

“We wanted to set the project up for its greatest success. First and foremost, we wanted to make this project the project of choice in the region,” he says. “We made sure we bid this just as the Shell cracker plant was coming to completion. There were 8,000 construction workers just 19 miles away from this airport that were going to be available around the time we went to market. We wanted to make sure they were choosing this legacy project. We also made sure that we had things like on-site parking for the workers. I can’t tell you how important that is to our workers to have on-site parking where they can walk directly onto the job site. That was not the case at the Shell project. We have health and wellness programs in place for all the team members. I’m also extremely proud of our safety program.

“We also made sure that we segregated the project site as much as possible from the daily operations of the airport. It was important to set that up to get the most competitive bids, because if contractors had to go through the TSA requirements in a secure area of an airport it would add significant costs.”

The TMP is operating under a unique safety partnership with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Hoback says the partnership allows OSHA to share industry best practices and provide timely feedback on conditions at the airport job site. He says it creates an unusual dynamic for OSHA at the TMP site.

“Most of the time OSHA is a regulatory agency that comes to projects in response to a problem. We have a partnership that is the first of its kind and we invite them out all the time. OSHA helps us make sure we’re implementing best practices that create the safest environment,” Hoback says.

For all the advanced planning and intentional decision making ahead of the start of the TMP, ACAA and its team could not have been prepared for what unfolded in March 2020. When the COVID-19 outbreak occurred, construction of the enabling packages had just begun. The design was at the point of being refined to begin bidding on the early packages.

“I think the biggest challenge was getting the project design completed during the pandemic. We had just done a big presentation the week before COVID hit. We were used to working collaboratively in person and then everything was remote,” Sponza recalls. “Suddenly, we were completing this airport design during a time when there was a lot of uncertainty in the world. It was a challenge to navigate that and anticipate how much the world was going to change and how much that would change the building we were designing.”

Hoback also pointed to the pandemic as the biggest challenge, but for the ACAA the problems extended beyond the design and construction challenges.

“We had started early enabling projects and were at 90 percent complete on the design, ready to bid the whole project when COVID hit,” he says. “We were also negotiating an airline agreement and it’s the airlines that are paying back the debt for the construction of this airport. We had finalized the terms and had signed contracts from two of our partners when the pandemic hit. At that moment the airlines needed to step back, and those agreements became void. Airlines are our biggest customers and we had spent six or seven years up to that point meeting monthly with them preparing for this project. It took about 16 months, but we got an airline operating agreement approved in the middle of a pandemic and it was unanimous. We were the first U.S. major airport capital program that was approved in a post-pandemic environment.”

Site work construction began in April 2021, with the terminal buildings getting underway six months later. Several of the project’s biggest packages bid in 2022 and 2023, meaning that the bulk of the bidding took place while cost escalation was on its way to a September 2022 peak of 24 percent. While that steep ascent has been followed by an equally steep decline over the past 15 months, the construction management team and ACAA had to be nimble to adjust to the conditions. Except for the initial structural steel package, which bid in spring 2021, virtually all the bid packages have come within expectations. The construction management teams were realistic about the market conditions and relied on the contractors bidding the packages to anticipate escalation in their bids.

“Each package has been a lump sum bid. The risk of escalation is on the prime contractors. There are no provisions for escalation built into the procurement,” says Jeff Turconi, who retired as president of PJ Dick Inc. in April 2023 but remains the executive manager at the joint venture for the TMP. “We expected contractors to understand the volatility of the market. Thus far, I don’t think it’s been an issue. Contractors have not come back to us and said that they were being hurt by unexpected escalation. It’s been well known that prices were going up. We have adjusted the budget. If you threw out the steel bid, most everything else has fallen in line with what we adjusted once we realized that the pandemic had caused a significant amount of escalation in a short period of time.”

With nearly all the major packages bid and awarded, the TMP has seen milder inflation of costs over budgets than the market in general. Hoback estimates that the escalation has been 12 percent, roughly one-third the rate of the overall market escalation during the same period. He attributes the better performance to extensive planning and regular revisiting of budgets ahead of bidding.

“In my mind, it was because we always expected the unexpected,” Hoback says. “We were able to control costs to a degree because we thought through all these things. I will tell you that when the pandemic hit, we had to make sure we had a construction management team that understood the industry, procurement, and the pandemic’s impact on the timeline. We had to build in extra time that we knew we were going to need.”

The adjustments made in response to the pandemic and its aftereffects – particularly the disruption of reliable lead times from the supply chain – put the project about six months behind the original schedule. According to Tara Connor, preconstruction manager at Turner Construction, the MMC will be completed in the fourth quarter of 2024. ACAA officials are still confident that the project will open 15 months from now. For the construction management team, the challenge will be compressing the remaining work with a team of separate prime contractors. That requires a different level of cooperation than if the project was being delivered under the control of one single prime contractor. Thus far, the process has been working.

“It’s been very collaborative. We have not been adversarial with the primes,” says Turconi. “There are issues with manpower and changes to the drawings. We are cognizant of the issues and are working with the prime contractors to help them get the job done.”

Assessing the Impact

As a construction project, TMP ranks only behind Shell’s polymer plant in Beaver County as the largest in 50 years. Past the halfway point in construction, with all the major bid packages awarded, the TMP is on track to cost $1.57 billion, including soft costs. The planning and design of the project occupied 563 jobs. During construction, the TMP will create 5,548 direct construction jobs. The project will have generated $1 billion in payroll compensation when it ends, resulting in $27 million in state and local income taxes (using 2021 dollars). Its total economic impact is estimated at $2.5 billion, resulting in 14,300 direct and indirect jobs.

For Christina Cassotis and ACAA, the TMP will result in an airport that functions in a way that is commensurate with the airline industry’s expectations and Federal Aviation Administration regulations. The new terminal and MMC should extend the life of Pittsburgh International Airport by 40 years. The more efficient airport should produce revenues over expenses that allow for the bonds that financed the project to be repaid without the kind of financial stress that accompanied the retirement of the 1991 debt.

None of these outcomes are bad, either for the traveler, the airlines, or the taxpayer. What separates the TMP from many other major public investments is that the rationale for the project does not depend on downstream effects that may not occur and that would be difficult to track. The modernization is not intended to be a catalyst for new development around the airport, at least to not any degree that the current airport location attracts development. The most significant downstream opportunity for development will come the disposition of the existing landside terminal.

“There is going to be a direct benefit for development opportunities once we demolish the existing landside terminal,” explains David Storer, director of commercial development for ACAA. “That will open up eight acres for development with proximity to the new terminal and the existing parking and roads. You’re talking about a fully pad ready site.”

The current landside terminal is designated for aeronautical use, since it directly supports the airport’s primary activities. To facilitate development of the land, once the terminal is demolished, ACAA will work with the FAA to change the designation of the property to non-aeronautical use. Storer suggests that the best use of the property may still be airport related.

“There was an office park recently developed in Tampa with terminal adjacency where the airport authority has its offices as well as many of the companies that support the airport. We have many firms that support our operations from engineering to operations,” he suggests. “Beyond that, I don’t know that we will see a lot of economic development. We built the terminal to control costs and improve the passenger experience. The terminal is not expected to attract new airlines.”

Regional real estate and economic development professionals mostly echo Storer’s view on the economic impact of the TMP. The consensus view is that the new terminal is a gain for the region, but the benefits will be felt by properties near the airport.

“I don’t anticipate any economic impact from that project other than that which we already see from our proximity to an international airport. It’s change, while important to us because it operates as an efficient and effective connection to the world, doesn’t have any additional impact,” says Lew Villotti, president of Beaver County Corporation for Economic Development. “I can tell you that because of its location and our proximity to PIT, we’re in discussions with several companies that we would not be without that proximity to the airport and its effective operations.”

“The new terminal should only help the regional economy, but any real impact to the local industrial real estate market would be more driven by air cargo than an improved passenger terminal,” says Rich Gasperini, principal and founder of Genfor Real Estate.

Gregg Broujos, senior vice president, leasing at The Buncher Company, agrees that the impact on the industrial market would be greater were the project to include an expansion of the cargo capacity. But he cites the improvements to passenger service as an enhancement of the benefits of proximity to the airport, something that has helped Buncher’s Neighborhood 91 development.

“Neighborhood 91 is an additive manufacturing ecosystem that we developed with Pitt. The first building at Neighborhood 91 was successful in part because of the adjacency to the airport,” Broujos says. “We have multiple additional buildings planned and the new terminal will be even more significant for those developments. We hear time and again from tenants of the first building that they can get materials from Germany in 24 hours. They can get people in from Germany for a tour and they can be to Pittsburgh and back within 24 hours. The new terminal will make that proximity for Neighborhood 91 even more important.”

“The new terminal at the Pittsburgh International Airport will certainly have a real estate and economic impact on Washington County,” says Jeff Kotula, president of the Washington County Chamber of Commerce. “In terms of real estate, the new terminal will serve as the northern bookend to the recently opened Southern Beltway with Southpointe serving as the southern bookend. With the ease and speed of access between the two locations, Washington County is strategically located for real estate growth along that corridor. We already see signs of that potential with Imperial Land Corporation’s investment at the Fort Cherry Development District and expect that additional industrial, commercial, and flex-space expansion to follow.”

“Considering the overall economic impact of the terminal modernization project, it will encourage more leisure and business travelers as well as provide an exciting ‘first impression’ for the Greater Pittsburgh Region,” Kotula continues. “Christina Cassotis and her team at the Pittsburgh International Airport should be credited with thinking big and, more so, smart about the modernization as the airport already drives $30 billion in economic impact to this region and with the new terminal, we expect that to increase.”

“Any additional traffic through that marketplace is good for us. A rising tide lifts all boats,” says Tony Rosenberger, president and chief operating officer of Chapman Properties, the developer of the 300-acre Chapman Westport three miles south of the airport off the Southern Beltway.

The airport corridor has been a focus of regional economic growth for 60 years. One-third of metropolitan Pittsburgh’s suburban office space is located between Green Tree and PIT. Findlay Township, where the airport is physically located, has been a hot bed of industrial development for two decades, aided by the designation of the Parkway West as Interstate 376. With the Southern Beltway now open as a limited access highway to Southpointe and the Shell Chemicals plant operational along the Ohio River in Beaver County, the airport corridor runs north-south as well as east-west. The airport is the nexus of the four-way corridor. A major improvement in the functioning of the airport enhances the corridor as well. For an economic impact, that may be enough. mg