If you build or sell houses for a living, you probably feel a bit cursed. As 2019 ended, however, there were signals that home sales and new construction were heading upward at a much steeper angle than the rest of the economy. By mid-March, the strong fundamentals of the housing market were overshadowed by the uncertainty of the Coronavirus COVID-19.

Traffic at existing homes dropped significantly in late March. Builders slowed construction of new homes. Sales and construction declined in 2020, but the housing industry is expected to lead the economic recovery that follows the end of the pandemic. It is, however, too early to be certain when that will occur.

That uncertainty is likely to linger through the spring of 2021. Even as evidence mounts that the social distancing and quarantine measures taken elsewhere are working to slow the virus, only time will reveal whether COVID-19 can be contained or will return several more times. Any economic outlook that ignores the virus ignores the elephant in the room. One that attempts to predict the impact is foolish. Instead, let’s look at the state of the economy before the outbreak, what we know about the impact, and what recovery from any downturn might look like – whenever that may occur.

The Outlook Before

In contrast to the start of 2019, the U.S. economy was pulsing in January 2020. Most economic data prior to the COVID-19 outbreak showed modest but continued growth. The first readings on the U.S. economy from the fourth quarter show that the economy grew at an expected slower pace. Gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 2.1 percent from the previous year, according to the first estimate of GDP growth from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). That matched the output during the third quarter. The slower second half of 2019 resulted in GDP growth of 2.3 percent for the full year, compared to 2018.

Employers generated 273,000 net new jobs in February on the heels of the same number of new jobs in January, outstripping expectations. Year-over-year wage growth was at 3.0 percent, marking the 19th consecutive month at or above 3 percent. The unemployment rate decreased again slightly to 3.5 percent. The labor force participation rate remained at 63.4 percent, its highest level since 2013. For 2019, the monthly average was 179,000 net new jobs, the smallest gains since 2011 but roughly double the rate of additions to the workforce.

Although consumer sentiment softened slightly in 2019 – mostly as a result of the general uncertainty about the economy – that sentiment did not appear at the cash register. Total consumer spending – as measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) data – grew by 3.3 percent during 2019. Total spending reached $13.4 trillion at the end of 2019, or 62.6 percent of the estimated $21.4 trillion in total U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) for 2019. Including additional investments in the economy beyond PCE, consumers account for 68 percent of the total U.S. GDP.

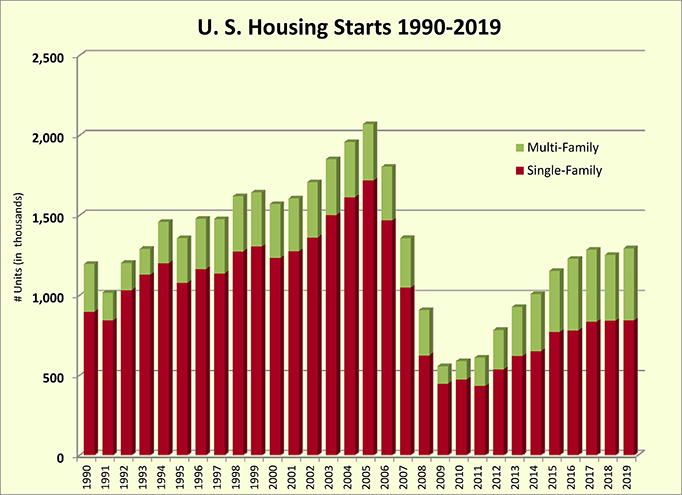

The February 19 release of housing starts in January had more good news. Although the data showed a decline of 3.6 percent from December, the 21.4 percent increase from January 2019 was an indication that new home construction was shaking off the dual headwinds of low lot inventory and skilled worker shortage. Building permits surged higher in January, foreshadowing a strong spring construction season. For the full year of 2019, the Census Bureau estimates 1.29 million new housing units were started. Construction of new homes in February slipped 1.5 percent, according to the March 18 Census Bureau report, but new single-family starts were up 6.7 percent from January to 1.050 million units annually. Single-family starts were up 20.6 percent year-over-year. Overall, housing starts in February were 39 percent higher than one year earlier.

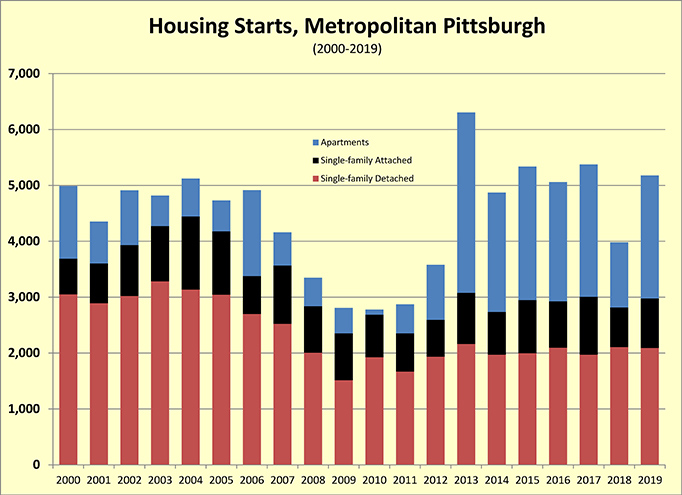

The Pittsburgh housing market remained very healthy but short on supply, both for new construction and existing homes. The supply of homes on the market shrunk further to 3.1 months. Construction of new single-family homes fell slightly to 2,957, down 27 units from 2018. There was a 4.7 percent decline in single-family detached homes, as builders continued to struggle to find available lots and buyers struggled to find homes priced below $250,000. New construction jumped 25 percent overall, due to an increase of 94 percent in multi-family units built.

The 2,200 units of multi-family was a return to the level of construction that has been the norm since 2013, reversing the decline to 1,164 units in 2018. With a backlog of more than 3,500 units of multi-family in the 18-month pipeline, it’s likely that 2020 and 2021 will see construction of at least 2,000 units. With Pittsburgh’s demographics supporting growth in the two cohorts that make up the lion’s share of renters – those over 55 and under 35 – the multi-family market has support for a few more years of increased construction.

Coming into the spring, the market fundamentals and low mortgage rate environment had the housing market poised for its best year since 2006.

“In the first month of 2020 alone, we already have achieved more than $350 million in home sales, which is up almost 18 percent compared to last year at this time,” said Tom Hosack, current president of West Penn Multi-List, Inc., and president and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices The Preferred Realty. “That’s a significant increase in closed sales volume, and it makes sense given the environment we had at the beginning of this year.”

When comparing January 2020 with the same time period in 2019:

Closed sales are up 10.94 percent (1,855 units in 2020 versus 1,672 in 2019);

Closed sales volume is up 17.63 percent ($350,732,270 in 2020 versus $298,154,384 in 2019);

Average sales price is up 6.03 percent ($189,074 in 2020 versus $178,322 in 2019); and

Home listings are up 2.45 percent (2,635 units in 2020 versus 2,572 in 2019).

“I think it’s a combination of factors that bumped up our sales this early in the year: a high demand for homes, low mortgage rates and a mild winter,” said Hosack. “It was encouraging to start off the year in this fashion, and while we hope 2020 will have strong sales, the current coronavirus situation will likely reflect changes in the first quarter and into the spring months.”

The Virus

The primary threat from COVID-19 is to human health. Government actions that ultimately lead to economic damage have and will be taken because the threat to public health trumps all else. That said, even short-term draconian measures will have tough economic reverberations.

Because COVID-19 was originally detected in China, early concerns about the economic impact of the outbreak were focused on China’s significant role in the global economy. This was particularly true of the global supply chain, much of which runs through China. The size of the Chinese economy, with its growing consumer middle class, increased the threat of global recession, as declining Chinese consumption due to quarantine there produced estimates of GDP growth as low as two percent.

Once the virus appeared elsewhere, however, it became clear that the decline in China’s economic growth and supply chain disruptions were not going to be the gravest problems caused by the pandemic.

The relative success of social distancing as a mitigation tactic led to widespread closings of businesses and cancellations of events worldwide. The resultant loss in revenue will mean that output during the late winter and early spring will decline precipitously. Based upon early data from China, Taiwan, Singapore, and Japan, the containment put in place in those countries will reduce economic output between five and ten percent relative to the previous year. Since most of this reduced output will come from reduced consumption, the recovery from the COVID-19 isolation will not be a surge that replaces lost consumption. Durable goods consumption could see such a surge after the crisis passes, but the loss of wages and wealth is sure to dampen the demand for automobiles and appliances for a while.

Put into perspective, the decline in GDP caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is certain to exceed the 4.5 percent decline that occurred during the 2008-2009 Great Recession.

Beyond the damage to GDP, the COVID-19 outbreak has a strong potential for triggering downstream financial shocks to the economy. Without financial assistance, some share of the workers who lose jobs will be unable to make loan payments. As defaults on car loans, credit cards, and mortgages increase, banks will find it necessary to tighten credit.

It is the cascading effect of the economic impact that presents the greatest risk to the U.S. economy. If consumers fear that the job losses caused by containing the virus are triggering a recession, they are likely to cut back on spending – even if they have not lost their jobs. The fallout from that shift in sentiment – rising unemployment, lower demand, increasing loan delinquency, business failures, and bankruptcy – will create a serious drag on the economy. Coupled with the dramatic drop in oil prices, the fallout from COVID-19 greatly increases the risk of recession.

Should a recession be triggered, the U.S. economy is in significantly better condition today than it was in 2008. Consumers are employed to a higher degree. Unlike in 2008, consumers are saving at a high rate, providing some cushion against tougher times. Corporations have used low interest rates and tax cuts to leverage their debt from $2 trillion to $7 trillion. That will make highly-leveraged corporations more vulnerable; however, corporate cash reserves are also high. Early government action to stimulate the economy has included provisions to aid with liquidity for corporations and small businesses.

There is a temptation to view this economic disruption similarly to the financial crisis of 2008. There are parallels. The threat to the general population of the U.S. seemed distant, even as news of the problems (subprime mortgage defaults back then) trickled into the media. The powers that be downplayed the severity of the threat initially or, at the very least, tried to focus on a silver lining, like the fundamentals of the economy. And like in 2008, once the problem fully surfaced, it changed rapidly and played out in real time.

Unlike in 2008, however, the current economic threat isn’t coming as a correction to bad decisions and malfeasance. Home values have been increasing by more than four percent annually for most of the past decade and jumped eight percent in 2019. Households aren’t overburdened by debt. Access to credit is better than most cycles and the cost of borrowing is cheaper than ever. Hosack sees a much better comparison to the period following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

“Essentially, the world shut down for two weeks following that event and the stock market went in the tank, but the housing market came back strong,” Hosack says. “What is amazing to me is that we are still selling so many houses. We had a home just go on the market and it had 12 showings and sold the same day. I think there’s kind of a general belief that this is a temporary thing and that the government is on top of it. People feel like there will be temporary pain but long term I don’t see the mindset that we had in 2008, when people were afraid to own a home again.”

Hosack’s observation was made early in the outbreak, before more extensive sheltering in place occurred. Assuming the demand for homes rebounds when the pandemic recedes, there will still be issues getting sales closed. County courthouses and recorder’s offices are closed and will have backlogs to erase. Township offices aren’t processing lien letters. Employment verification will be slow to accomplish. And lending will likely not be as smoothly completed.

Lending is also being impacted by the changing economic environment, most specifically the sudden rise in unemployment. The speed with which the pandemic moved through the economy caught people in the midst of buying or refinancing a home when bad luck hit.

“We have seen several cases of people who had started the mortgage purchase or refinance process and were unfortunately one of the people who have been laid off. Those applications are on hold until they return to work,” says Lisa Clore, senior vice president & director of mortgage lending at Community Bank. “Purchases are still taking place in this area right now but I do see it slowing. Buyers can’t get out to look at homes and construction has just stopped.”

The Outlook After

In the best-case scenario, in which things return to normal, the pandemic will cause a significant disruption to the global economy. During the first few weeks of the outbreak in the U.S. emotions ran high, as bad news became worse news. Our worst fears seldom become reality but it has become clearer that some of the economic fundamentals will be changed by COVID-19.

Most obvious of those fundamentals is that incomes will be lower in 2021. Higher unemployment means less discretionary income overall. Businesses will be less profitable in 2021, so paychecks may shrink and bonuses will be smaller, or nonexistent. Lower interest rates mean that those on fixed incomes from investments will see smaller yields. The steep decline in the stock markets, however short-lived, will reduce the income that people can take from their investments.

The stock market decline also reduces the amount of individual wealth that exists. That means some people may put off retiring for a while. It also means that some potential home buyers may put off buying because their savings are lower.

There are also some economic fundamentals that the pandemic will not change. U.S. population is still growing. That means demand for goods and services is also still growing. In a market-driven economy, opportunity exists for those with ambition and ideas. There are still countless problems in the world that require solutions. The economy, particularly the Pittsburgh economy, was performing best where emerging technologies were tackling those problems. The terrible virus itself will ultimately prove to be a problem that is solved, maybe by one of the Pittsburgh-based institutions or companies working to end the pandemic.

In the final analysis, it is the employment situation that will determine the arc of the recovery once the COVID-19 pandemic has abated. There will be layoffs for workers in industries that simply aren’t working while social distancing occurred. If measures to compensate these workers are adequate, the recession could be milder than expected. Fewer businesses will be forced to close. Fewer loans will be in default. Should business shutdowns and layoffs deepen, the cascading effect of losses will deepen the downturn.

One month into the economic shutdown, the impact on the housing industry is apparent. Unemployment claims were up nearly five million by early April 2020. Home purchase mortgage applications fell 12 percent during the last two weeks in March. Housing starts declined in March, after being up 24.7 percent year-over-year during December, January, and February. Expectations for new construction, which was on pace for 1.6 million units, are for new starts to decline below 1.2 million units in 2020.

Such a deep recession would more closely resemble a typical recession, even if the catalyst for the recession was unusual. Throughout U.S. history, recessions have been triggered most often by slowing demand. Business slows and layoffs follow. After that, credit begins to deteriorate. In nearly all recessions, slowing demand is accompanied by other negative factors, like rising loan delinquency, plummeting property values, or skyrocketing vacancy rates. None of those conditions were present ahead of the current crisis. That means recovery will be aided by factors that provide a stronger economic base.

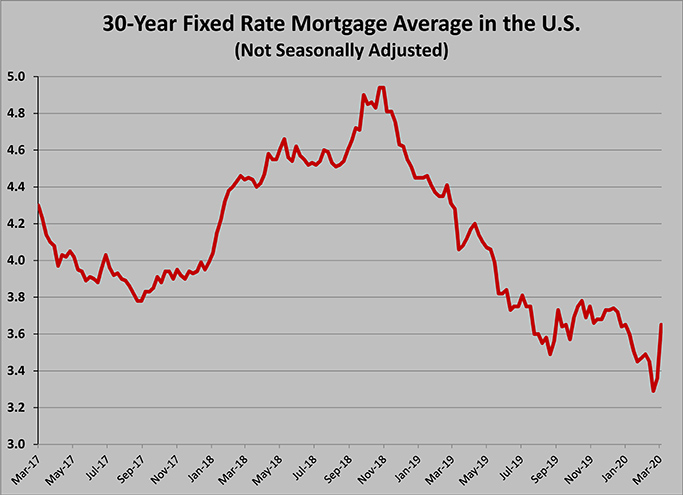

One of those factors is the low interest rate environment. The Federal Reserve Bank responded quickly to the outbreak by dropping the Fed Funds rate twice, ultimately to the near-zero levels that followed the financial crisis. As usually happens during a global crisis, investors also flocked to buy U.S. Treasury bonds, which drove interest rates on all debt to record low levels. The low interest rates will help the government fund its recovery efforts. Low rates will also help the housing market recover.

The Mortgage Bankers Association reported on March 11 that there was a 79 percent jump in refinancing activity in the week after the Federal Reserve Bank cut its Fed Funds rate by half-percent. Refinancing activity was up 479 percent compared to last year at that point. For the consumer, the refinancing means a big improvement in the household balance sheet. Cost of home ownership is lower. There’s more discretionary income. Mortgage indebtedness is cut to 15 years or less for millions. The Mortgage Bankers also reported that there had been a 6 percent increase in home purchase mortgage applications, which was a 12 percent increase year-over-year. Likely that increase would be greater if there was a normal inventory of homes for sale.

“Right now, we’re still really busy with refinancing,” noted Lisa Clore on March 31. “It may slow down in the next week or so but we’re still seeing a tremendous amount of people doing refinancing because the rates are so low. And people are afraid that after this is over rates are going to climb, so they are taking advantage of the opportunity right now.”

Inventory of homes for sale and available construction lots also support recovery, in contrast to 2010. Nearly 9 million homes were foreclosed upon or disposed in short sale during the mortgage crisis that stretched from 2007 until 2009. That created an overhang of inventory that took seven years to absorb. But since the middle of the last decade, inventory of new homes fell steadily. Baby Boomers have stayed in the family home longer. New construction development has not returned to historical volumes. In January 2020, there was a three-month supply of homes for sale, both nationally and locally. That’s about half of what a healthy housing market needs to support the demand for buyers.

Hosack believes that some of the demographic obstacles were beginning to ease, which would free up existing homes for the normal generational transition of family homes.

“We are starting to finally see new construction of the type that the Baby Boomers need to downsize. That’s the patio home and there hasn’t been enough of that in that market,” he says. “One of the other side effects of the Millennials staying at home longer is that their parents have stayed in the house longer rather than moving down. Now that the Millennials are buying homes it’s triggering more downsizing. We’re starting to see a little more of a balance in the market.”

Scarmazzi Homes markets most of its homes to the empty-nester market. Paul Scarmazzi explains that his company has been intentional about developing more lots to meet demand, part of a three-year strategic plan

“We have between 300 and 400 lots on the books in various stages of development,” he says. “We have a large subdivision of 107 lots on the planning agenda in Union Township. We have 30 lots in the process of starting in Cecil Township and another 50 or so lots in Chartiers Township in a plan we are selling out of. We have new lots in South Park. We are looking to expand our geography.”

Chad Weaver, president and CEO of Weaver Homes, has also led his company on an effort to increase the amount of product available for the Baby Boomers who will trade the family home for an empty-nester, low-maintenance lifestyle. Weaver Homes has grown steadily over the past five years, pulling permits in 2019 for 110 homes, the fourth highest volume of any Pittsburgh builder. Weaver says their activities last year positioned the company for more demand.

“Coming into this year we had more plans and more lots for that [empty-nester] product than at any time in our history,” he says. “We’re actually set to close on another piece of property in Sarver for an 80-unit plan. We were waiting for our NPDES permit so obviously when everything shut down, we were still waiting on that. We’re putting that on pause. We have a couple of other pieces of land that we have under option that will also pause until we get to a new normal.”

When the virus-induced recession ends, it’s likely that that supply will have grown, as some number of unemployed homeowners will be forced to sell. Pent-up demand for home sales has existed since 2018, however, meaning that the pool of buyers looking will be larger than during the early stages of a “normal” recovery.

“Pittsburgh is going to do what it’s always done; and that is, it doesn’t boom and it doesn’t bust. We’ve always fundamentally been a market in balance,” says Scarmazzi. “Sooner rather than later coming out of this will see a return to what will be the new normal.” Weaver believes the market for Baby Boomer buyers is deep enough. We are less sure about how the recession will impact the pool of buyers to whom the Boomers will sell.

“This year we thought we were going to have about a 50 percent increase, based upon all the land and lots we had available. Of course, that’s going to change,” he predicts. “My only concern about demand is that the Baby Boomers all have a house to sell. Typically, they’re selling those homes to a Gen. X or Millennial buyer. With the unprecedented amount of unemployment out there it’s hard to know who is going to be in a position to buy a home going forward. The demand for our product will still be there. Even during the downturn in 2009 there were still buyers out there, but the longer this recession goes on the harder it may be for the people who will buy the empty-nesters’ home.”

The question that will remain is the extent to which the measures taken to fend off the COVID-19 virus damaged the strength of the U.S. economy. These are uncharted waters. It’s possible that the direst predictions of the duration and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic may yet come to fruition. The 2008-2009 recession was devastating to individual wealth and financial security. It took several years for the American consumer to get their collective house in order. The recession that is likely to occur in 2021 will begin with fewer people out of work, fewer displaced from their homes, and far fewer facing years of overhanging debt to repay. When U.S. employers begin hiring again, consumers may not be coming out of as deep a hole.

That would be good news for the U.S. economy and the housing market. mg