Downtown was becoming a more vibrant live/work/play center throughout the 2010s, but the “work” part of that equation had begun eroding in the middle of the decade. Once the third largest home to Fortune 500 companies, Downtown Pittsburgh lost tens of thousands of daytime workers when industrial giants moved out in the 1980s, even as five new buildings were built. After stabilizing and rebounding in the 1990s, office occupancy rates soared in the mid-2010s. Those single-digit vacancy rates belied the coming trend of subleases and structural downsizing that was to come later in the decade. The pandemic was the last straw.

In the fall of 2022, the effects of the pandemic are still palpable from 9:00-to-5:00; however, the vibrance of nights in Downtown has returned. Restaurants and bars are full. The Cultural District is selling out again. Streets are full of residents walking dogs and suburbanites taking a night on the town.

If you had asked a civic leader for a vision of a vibrant Downtown 20 years ago, chances are they would have described a scene like you can find on any given evening. Even the most optimistic promoter of Downtown might not have expected the number of apartments and condos being occupied. It is safe to say that no one would have predicted that 80 percent of the daytime workforce would be absent.

Leaders now must set a new course for Downtown Pittsburgh. With any luck, the market will follow. That does not always happen. When the city got out of the way and let developers set the vision, residential flourished and lifestyle amenities followed. But the health of the office market Downtown was masked by several factors that were unrelated to the factor that drives office occupancy: job growth.

The job growth that is anticipated in Pittsburgh in the coming decade is unlikely to be in sectors that will gravitate to Downtown. It will be tough to move the needle on the office occupancy levels Downtown, even if everyone returned to the office by Thanksgiving. That does not mean that Downtown faces a bleak future. What the market has already begun to demand – more residential Downtown – is being met by converting more of the office buildings to apartments and condominiums. Public- and private-sector leaders seem to have recognized this. Policies and incentives are beginning to follow. It is clear that the future of Downtown Pittsburgh will be more residential, more 24/7. That will not be a bad thing, just a different thing.

The Office Problem(s)

The principal problem facing the Downtown Pittsburgh office market is the same problem facing office markets everywhere: fewer people want to go to the office to work. That change in attitude, brought on by the necessity of working from home during the pandemic, may be temporary in nature; however, there are other forces acting as headwinds to office occupancy Downtown.

Beginning with Citizens Bank’s 2015 announcement of its intentions to vacate its space at 525 William Penn Place, multiple corporations relocated from Downtown or downsized dramatically. Few, if any, of these changes were the result of a negative Pittsburgh experience, but the market nonetheless saw almost two million square feet of space available for sublease. The impact of this was muted because of three positive market influences a decade earlier. UPMC added more than a million square feet of absorption to Downtown when it moved its headquarters from Oakland to 600 Grant Street. Point Park University acquired and repurposed a handful of obsolete office buildings between Fourth Avenue and the Boulevard of Allies. And a dozen office buildings were converted to hotel or residential use.

The vacancy rate plunged in Pittsburgh more because the denominator shrank. The numerator – the number of people occupying offices – remained almost

the same.

Pittsburgh remains a home to a large number of law firms, accountants, and financial service providers. That is a remnant of the demand created by the industrial corporations that called Pittsburgh home. Indeed, many of the firms located in Pittsburgh today still serve those industrial giants all over the world, even though the clients have not been in Pittsburgh for decades. Improvements in technology reduced the number of administrative staff needed. Changes in culture and design shrank private offices and eliminated walls. The net result has been a reduction in demand for space, even as the firms in Downtown have expanded.

These trends in office space were becoming impactful before the pandemic. Downtown’s most recent big lease news is a perfect example. Dickie McCamey & Chilcote announced the signing of an 80,000 square foot lease in Gateway Center, a reduction of 20 percent from its existing space at the same time the firm reached the 200-attorney level for the first time.

Since March 2020, companies providing professional services, such as attorneys, accountants, and bankers, learned how to be effective for their clients while working outside the office.

Another factor making downtown occupancy more difficult is the increased competition from the areas just beyond the central business district (CBD), especially the Strip District. Developments like 3 Crossings, District 15, and Vision on 15th, have grabbed tenants that might otherwise have opted for the Golden Triangle, including a couple firms that were located there. While this trend effectively expands the perception of what is “Downtown Pittsburgh,” it draws tenants away from the traditional downtown offices.

“When you see three million square feet being built on the periphery, where are those tenants coming from?” asks Jeremy Waldrup, president and CEO of Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership (PDP). “They will pull from the Golden Triangle and the 25 million square feet of office here.”

Those are several strong headwinds working against occupancy levels in the CBD. None compare, however, to the disruption to office life that came from the pandemic. For all the regional market issues that might be making the downtown office market more difficult to lease more fully, the biggest problem has a simple solution: people need to return to the office. It is a simple solution that has thus far eluded the market.

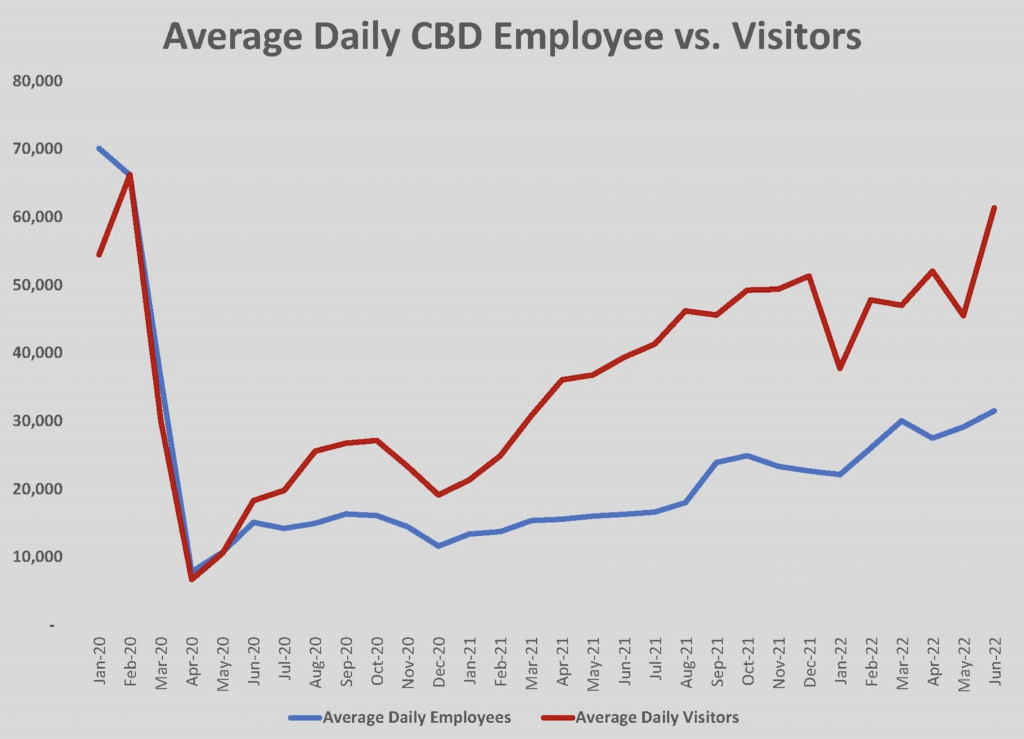

The impact of work from home, either as a full time or hybrid policy, is dramatic. Daytime visitation to Downtown is about 77,000 people now, compared to 137,000 a day before the pandemic. For a submarket in which 77 percent of building stock is office, one of the highest shares of office space among major metropolitan cities in the U.S., that is a dramatic change.

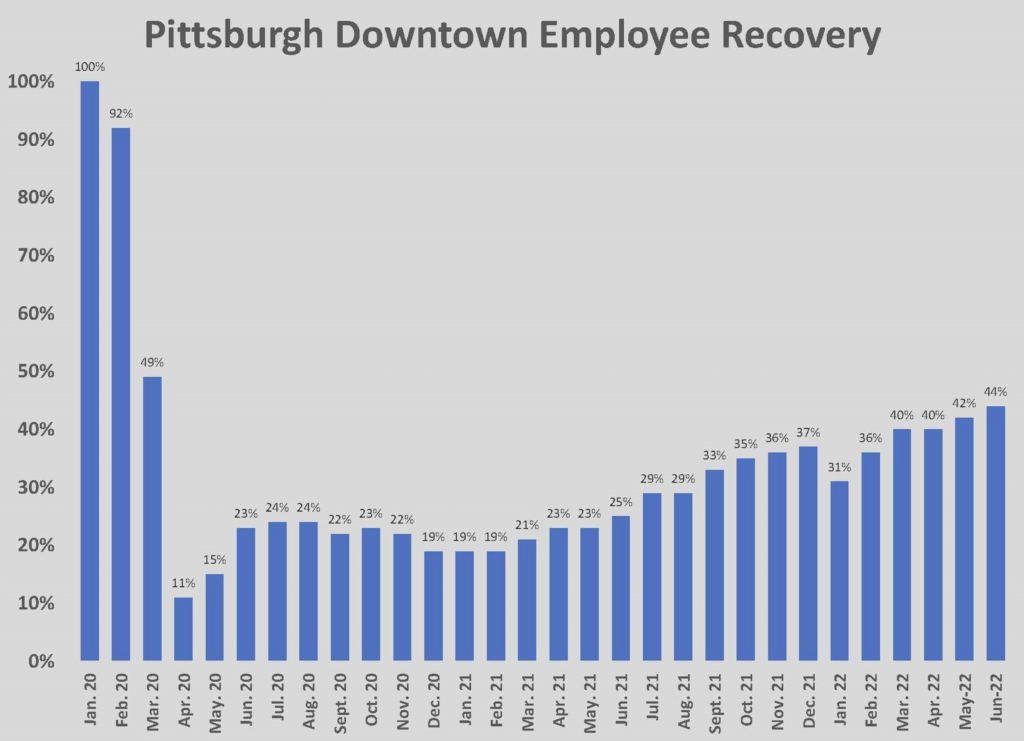

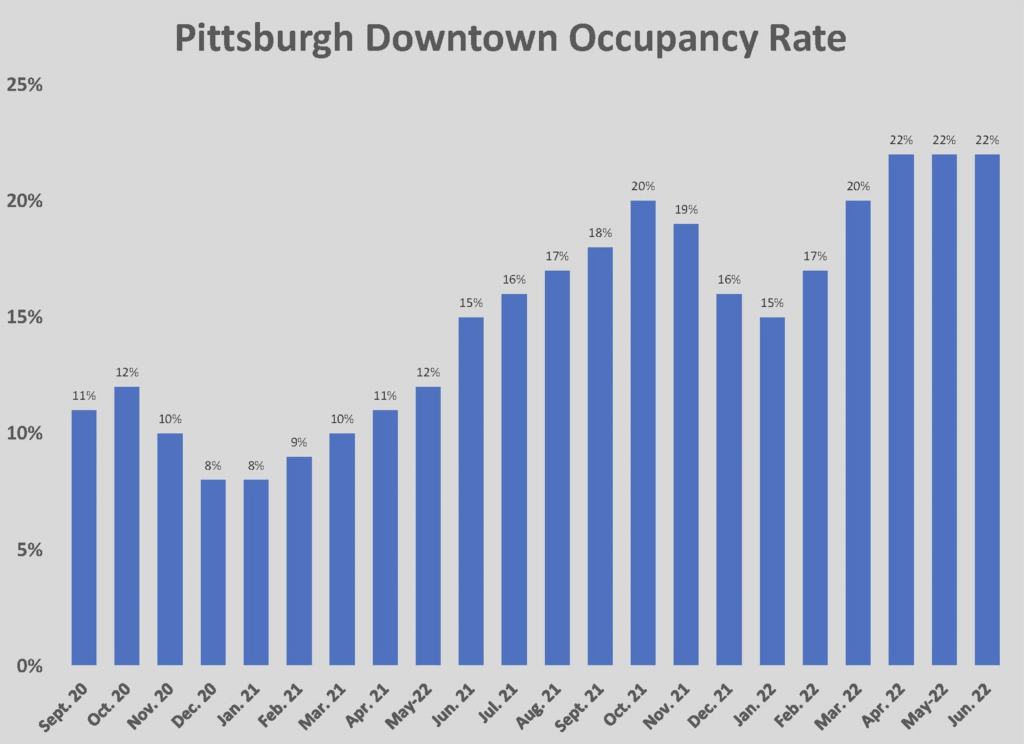

Waldrup notes that the return to office has crept up slightly in recent months but has essentially been range-bound around 20 percent since the late summer of 2021. The share of employees who have returned to work Downtown is more than double that number, reaching 44 percent in June. The disparity between those numbers underlines the headache for downtown landlords and tenants. While nearly half the employees have come back to the office, only one in five occupies on any given day.

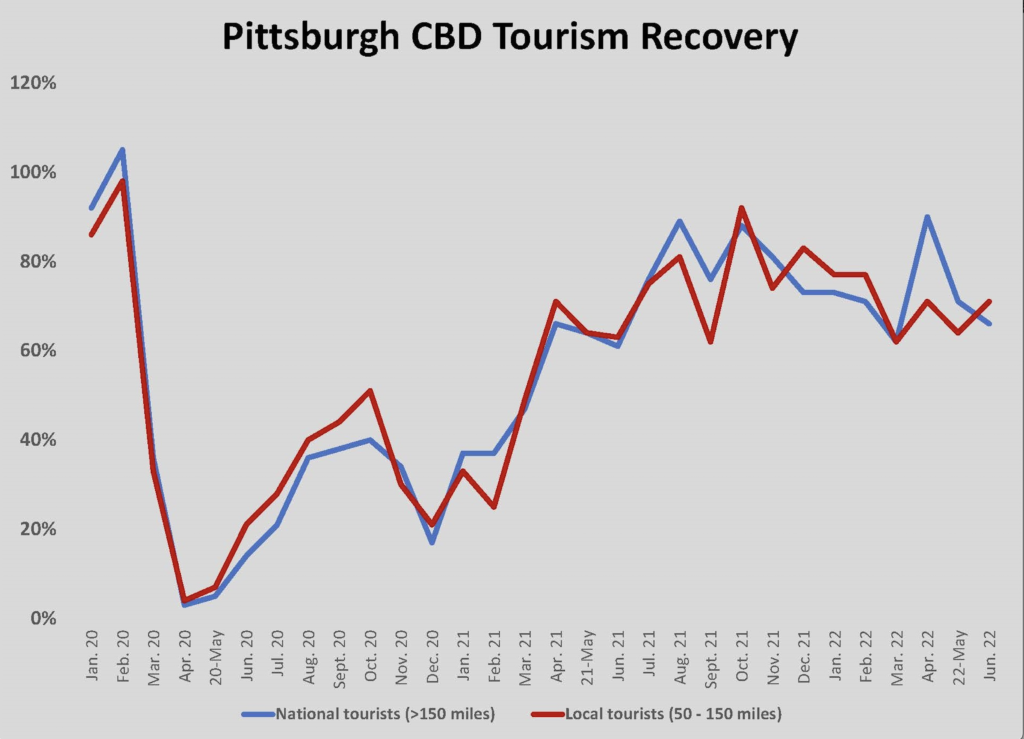

In contrast, the level of leisure and travel activity in Downtown have returned almost entirely. Tourism recovered to between 80 and 90 percent during the 2021 football and holiday season, dropping off to the 70 percent range in recent months. The number of daily visitors to Downtown has mostly recovered to pre-pandemic levels, however, suggesting that people from around the region are returning to enjoy the lifestyle amenities in Downtown. One metric, the number of restaurant seats occupied, sits at 115 percent of the 2019 level.

If you have visited Downtown in the evening or on a weekend, the vibrance that was palpable in 2019 is there. During the day, however, the CBD does not have the hustle and bustle of three years ago. That has changed how landlords are operating.

“Things are going to start changing and have changed already. The issue right now is that we don’t know what things are going to change to. There has to be a strong office market in Downtown Pittsburgh, and I think there will be. It will take some time to adjust,” says Gerard McLaughlin, executive managing director at Newmark. “If you own a building that is 80 percent occupied you should do everything in your power to attract tenants to your building. That means modernizing the building, adding amenities, and working with your leasing team to make the building as attractive as it can be.”

McLaughlin notes that the shift to work from home swung the market in favor of the tenants, particularly the employees of tenants. The need to upgrade and “amenitize” buildings is a response to the challenge of retaining workers and attracting them to return to the office, even if on a hybrid basis. Tim Goetz sees corporate occupiers responding to the shift.

“We are seeing longer term leases again. In return, tenants are looking for amenities for their employees. The process has been more democratic. They are asking their employees what they want to see after working from home for two years,” explains Goetz, who is managing director for Cushman Pittsburgh. “The landlords are committing to collaboration spaces, fitness centers, storage space, conference rooms, and other amenities to attract credit worthy, quality tenants. Landlords are going to need to do that if they want to compete. If tenants are trying to retain and recruit, they will need workspaces that are attractive to workers.”

The new balance of market power means that the decade-long upward trend in CBD rents is likely to end. Office rents in Downtown were the highest in the region, but Class A buildings in Oakland and the Strip have commanded higher rents than those in the CBD for several years. Competition from those submarkets will continue and the focus on employee wants also has employers evaluating their space needs differently.

“We don’t have a lot of new companies coming into Downtown. When leases come up for renewal, companies are looking at how they are using their space and often now are looking at using less space,” notes McLaughlin.

“We are seeing landlords provide contraction rights, so tenants have flexibility if they make a longer-term competitive commitment. We are seeing landlords be more aggressive to retain tenants. That will bring rates down a bit,” agrees Goetz. “On the other side of the coin, tenants that are moving and willing to make a long-term commitment understand that landlords are making a long-term investment and need market rates for that space.”

Goetz emphasized that the market was still feeling its way through unknown territory and that tenants were still searching for what their needs will be as leases turn over. The way forward is unlikely to be known until that search ends. In the meantime, the conditions will challenge landlords to retain tenants and reward investors.

The Downtown Office Solution(s)

Few observers of the office market or Downtown Pittsburgh expect a solution to the underlying problem to emerge. While a miraculous return to office occupancy would be welcome, landlords in Downtown would still be challenged with the long-term structural trends. It is difficult to suggest what might trigger a return to normal office occupancy again. Some suggest that a recession, which leads to higher unemployment, might make workers less comfortable about their absence from the office, while others believe that a reversal of the trend will come if working from home begins to feel like missing out – maybe literally when it comes to raises and promotions. It may also be that employees will not feel obliged to change unless they are compelled to by employers.

“A return to the office will have to be driven by the big employers,” says Jim Scalo, CEO of Burns Scalo Real Estate.

One trend that will not be driving occupancy Downtown is new development. While there are speculative offices in development and under construction in Oakland and the Strip District, there are no plans for new construction Downtown. The flight to quality is simply outweighed by the difficulty and cost of construction in the CBD.

“There are issues working Downtown that you don’t have in the suburbs. There’s a lack of lay down issue area. There are more labor issues. And then there’s the time involved,” says Scalo. “The biggest issue in town today is still permitting. We can do three projects in the suburbs in the time that we can do one in the city.”

“When you’re building in Downtown it’s that much more difficult, especially if you’re trying to be sustainable. There is little room for laydown and staging so you need to make more trips to bring material in. There is little room for cranes. The duration of the project is longer in the CBD because of how you stage, how you deliver, and the number of hours you can work,” explains Steve Guy, president and CEO of Oxford Development Co. “In Downtown, you also have to go more vertical, and the more vertical you go the cost per square foot increases and the efficiency decreases. The cost per usable square foot is going to go up in a CBD or urban core environment. In the urban fringe there is a natural benefit of at least three percent, probably five to eight percent, over what you can build in an urban core.”

Guy argues that the math does not work for investors in the current market conditions.

“We all compete for the same rental dollars. We don’t get better financing or cap rate in the CBD. When you’re looking at the same rent dollar that extra $20 or $40 or $50 per square foot is a real differentiator in the yield,” says Guy. “If you have to charge the same rent, your investors have to be willing to accept perhaps 150 basis points lower yield. Even if I believe the demand side opportunity is equal, why would I invest where I would get 150 basis points lower yield?”

Steve Guy’s rhetorical question assumes that demand for office space Downtown is equal to other parts of the region, an assumption that is difficult to accept. None of the growth sectors of Pittsburgh’s economy – healthcare, robotics, artificial intelligence, or life sciences – are natural fits for high-rise office settings. (In fact, it’s easier to argue the opposite.) In general, office demand is weaker now regardless of the location. But demand for residential space continues to grow and that may provide the solution to the downtown office problem.

There are 7,000 residents living in Downtown in 4,100 dwelling units, most of which are rentals. That is roughly twice the number of people who lived Downtown in 2000. The vacancy rate in downtown apartments is six percent. After a decade of adapting old offices and building new units – led by PMC Property Group from Philadelphia and the Piatt Organization (then Millcraft) – developers cooled on the CBD. That has changed since the pandemic.

PMC has started work converting the former Allegheny Building on Fourth Avenue into 177 apartments. Roughly 700 units in three major projects on the verge of construction in the Golden Triangle. The Former GNC headquarters building at 300 Sixth Avenue is being converted into 254 apartments by Victrix LLC. Douglas Development has proposed 142 units in the former Easter Seals Building at 642 Fort Duquesne Boulevard. City Club Apartments are 300 units of new construction being developed by Jonathan Holzman at 305 Wood Street. Another 125 units or so are proposed in numerous smaller buildings. That is the first wave of new residential.

Recently, Hertz Investment Group floated the idea of converting 3 Gateway Center to 300 residential units and Rugby Realty announced it was looking for a development partner to convert the 44-story Gulf Tower into a mix of luxury hotel and roughly 200 residential units on the upper 25 floors. In announcing Rugby’s plan, Aaron Stauber referred to research that suggested that demand existed for 5,000 or more additional residential units in the Golden Triangle.

Jeremy Waldrup sees the conversion as a needed boost for the residential component of Downtown, as well as for the troubled office market trying to rebound from the pandemic.

“Taking 500,000 square feet of commercial office off the real estate rolls will help the market. It will push current tenants in those spaces into other buildings. We are seeing the flight to quality play out in the leases that expired in the last two years, not just in Pittsburgh but everywhere,” he says.

Waldrup thinks the relatively low number of downtown residents has impacted the return-to-work metrics in Pittsburgh, at least when compared to other cities with more residential downtown areas.

“Look at the residential makeup of Philadelphia. It has quadrupled over the last 20 years. Philadelphia is 90-plus percent return to work not because they have more people in the office, but because they did not lose people who worked and lived downtown.”

Leonard Klehr, principal at Lubert Adler, is based in Philadelphia and saw that disparity as an opportunity when his firm looked at taking control of the redevelopment of the former Kaufmann’s into apartments.

“Pittsburgh is not a foreign market to us. We know about it and think about it. The Kauffman’s development was in a distressed situation. The developer found his way to us, and it was the kind of transaction that Lubert Adler specializes in,” Klehr recalls. “We certainly had our questions about demand, especially given that the transaction took place during the pandemic. Traditional urban residential is dependent upon job growth and there wasn’t any at that point. Lubert Adler has a history of adaptive reuse in a number of cities, and we wanted to take a shot at Pittsburgh. It was behind its sister city, Philadelphia, in developing residential units Downtown.”

The Kaufmann’s Grand project and the conversion of the Commonwealth Building occurred during the lull in residential development in the early 2020s. Those properties now have waiting lists of prospective renters.

As Downtown Pittsburgh sees more residential development, the developers will run into conflict with the desire of civic leadership to bring more affordable housing into the city. As Klehr noted, adaptive re-use of obsolete office buildings is usually complicated and complicated costs more money. Mayor Gainey launched the Downtown Conversion Pilot Program on July 1 to create opportunities for workforce housing by offering incentives to developers for up to 10 percent of the units and committed $2.1 million in American Rescue Plan (ARPA) funds to aid in financing. Though well intentioned, the program will need to bridge a larger gap in financing than the current funding level.

“This conversation about commercial conversion to residential will continue to be a priority for us. We have been lobbying the city, county, and state to provide additional funds for this. Right now, we have a $9 million commitment and we’re looking to grow that to $50 million,” says Waldrup. “We’re interested in creating workforce housing, not just luxury units but opportunities for our service workers, healthcare workers, and restaurant workers to have access to downtown housing. That would be an amazing opportunity to provide but something that downtown landlords haven’t figured out yet. We see it as a boon to recruiting healthcare workers or other service providers to our region. Imagine the opportunity to offer a 20-something person just graduating from college to work and live Downtown instead of being forced into a suburban setting.”

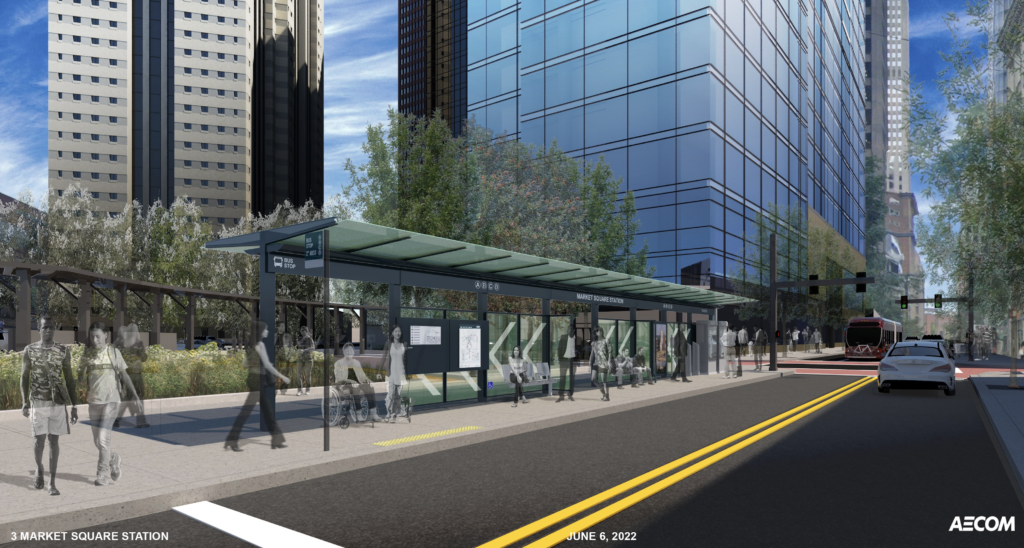

Another regional improvement that could facilitate the development of more housing, particularly workforce housing, is the bus rapid transit system (BRT) that will connect Downtown to Oakland and other eastern Pittsburgh locations that are employment centers. The downtown phases of the $291 million project are scheduled to go out for bid, with construction starting in spring of 2023. The new system will be operational before the end of 2024

The BRT route will bring the buses west on Fifth Avenue into Downtown and east on Sixth Avenue to the Steel Plaza Station, after which buses head east to Oakland and beyond on Forbes Avenue. Adam Brandolph, public relations manager for Pittsburgh Regional Transit (PRT), notes that all turns made in Downtown will be right turns, eliminating the traffic problems that result from buses turning left. The pattern should reduce congestion from bus traffic and speed up the trips from downtown stations to eastern Pittsburgh destinations.

Stations will be built along Fifth Avenue at Ross Street, William Penn Place, and at Liberty Avenue, opposite Market Street. Along Sixth Avenue, the stations will be located at Wood Street and Steel Plaza on Grant Street. The latter two stations will be integral to connecting the BRT to the PRT’s light rail system.

“The BRT will connect with the light rail system at the Wood Street and Steel Plaza stations,” says Brandolph. “From there riders can travel seamlessly to the North Shore or destinations in the South Hills.”

If these efforts to develop and attract more residents and visitors to Downtown are successful, PDP recognizes that there will be increased focus on public safety and infrastructure in the CBD. After a decade of advocacy, funding has been freed to complete the redesign of Smithfield Street, which will improve pedestrian safety and traffic flow. Waldrup jokes that Downtown Pittsburgh needs another handful of similar projects and expects the public infrastructure upgrade to increase private investment. He also expects improvements in human services Downtown.

“We’re focusing on Downtown being a welcoming. We will continue to focus on clean and safe. We’re working with police department and homeless outreach providers to provide services. Things have changed. We have more people sleeping on our streets than we have in recent memory,” Waldrup acknowledges. “There are a lot of organizations interested in supporting those individuals. The Second Avenue Commons shelter facility will open in mid-September. That should be transformative to providing services for folks in a low barrier setting. We don’t have that now.”

Clean and safe are important ingredients for attracting retailers, another important component of developing an 18-hour Downtown. Retail (including restaurants) was decimated by the COVID-19 mitigation measures in spring 2020 and the climate for shopping and dining did not improve much until after vaccines were widely distributed. Waldrup reports that 30 percent of the ground floor tenants went out of business Downtown in 2020. New businesses have been backfilling those spaces and the survivors of the pandemic have seen demand recover.

“It’s an interesting time for retail and restaurants. One of the answers we gave over time for not having certain retail Downtown was because there were not enough people to support it. Now the retail and restaurants are improving and it’s with less people. There are more customers but people that are working Downtown are not most of the customer base,” says Jason Cannon, first vice president at CBRE.

Adele Morelli, owner of Boutique La Passerelle, echoes Cannon’s observations. Morelli says she took advantage of any available grants and incentive programs to survive 2020 and built a new website that gave her customers a way to buy without visiting the store. When foot traffic returned in 2021, she had a record year with a different clientele.

“2021 was a building back type of environment. PDP continued to have events and Visit Pittsburgh drew people into the city; so, while we lost our main client base of women working Downtown, we gained clients from people who were visiting Pittsburgh,” Morelli says. That’s my biggest new client base. Every day someone comes in who is visiting Pittsburgh because people are doing more regional travel by car.”

The synergy between residential development and retail is as real in Downtown Pittsburgh as it is in Cranberry Township. Downtown office workers can support retail and restaurant businesses, but the daytime workforce in Pittsburgh was no longer large enough by the mid-1990s. Today, those businesses are thriving with a fraction of the daytime workforce as potential customers. The current environment proved attractive enough for Target, which is devoting half its floor space to groceries and staples.

“The timing of the Target deal was kind of odd because of the pandemic, but I think it gave people a sense of comfort that even in that uncertain time there were companies willing to commit to Downtown; and it was one of America’s favorite retailers,” says Cannon.

Downtown has changed more in the past two years than in two decades. As a 24/7 neighborhood, the changes have been incremental, almost unnoticeable to the untrained eye, except between 8:00 AM and 5:00 PM. But those changes have been dramatic. Office buildings are mostly empty most days of the week. Fewer restaurants are open at lunch. You can get a parking place any time of the day. Rush hour is not that rushed.

It is possible, maybe likely, that Downtown Pittsburgh in 2030 will look like 2019 looked during the workday. It seems foolish to predict when or how people will return to working in the office again. Until the new normal of office occupancy emerges, landlords and office tenants will be challenged to match space and needs. That will be true anywhere. If, in Pittsburgh, another dozen or so office buildings get a new life as an apartment or condominium, the commercial real estate market will benefit. It is worth remembering that Downtown Pittsburgh is home to 20 million square feet of office space. There is room for changes to occur.

Gerard McLaughlin believes that the basic value of the office – to offer a place where workers can collaborate to solve customer’s problems to a profitable end – is unchanged. He reminds us that the Downtown Pittsburgh office market has seen troubled days before.

“Pittsburgh is very adaptable. We went from 1980 having all the Fortune 500 companies to very few by 1995,” he says. “We’ll adapt to whatever the future brings.”

“We will get back to where the economy was pre-pandemic. Will offices look the same? Probably not. Once we all got a taste of working from home that became a game changer. Landlords will figure it out as well,” agrees Goetz. “How much residential can we have in the CBD? It would be great to increase that core of residents. It is a cycle, but we are resilient in Pittsburgh.” mg