How do you measure the health of a region? Vital signs like a strong job market, safety, and affordability all come to mind. But there’s another key question: how well does the region move? Transportation is the engine that drives economic development and vibrant communities. While Pittsburgh is exploring innovations to improve traffic flow on its roadways, it’s also abundantly clear that Pittsburghers want multi-modal means of transit. They want bike lanes. They want faster buses. They want more options to efficiently get from point A to point B.

The Pittsburgh region already has a robust transit community. Yet modes of mobility change. People’s transportation wants and needs change. Fortunately, the city has demonstrated ability to change—witness its evolution from a hazy steel town to a city hosting abundant cutting-edge financial, technological, and healthcare companies. Changes to make Pittsburgh more mobile are transformations to embrace, ones that will define its path forward in the 21st century.

In its own way, keeping transportation and mobility at the forefront of Pittsburgh’s progress agenda is a nod to the city’s history. “This was a region that was built around transportation. Pittsburgh is here because of the rivers. They were the superhighways of the past,” says Ken Zapinski, senior vice president of energy and infrastructure at the Allegheny Conference on Community Development. Pittsburgh already shows strong signs of transit health. Roughly half the people who work in Downtown Pittsburgh or the immediately surrounding areas take public transportation to work each day, a percentage that few U.S. cities can match. And the city’s streets showcase the very future of automobile transit. Pittsburgh now contains several companies working on autonomous vehicle development, including Uber, the ride-sharing service. Uber’s self-driving vehicles, with their rotating rooftop sensors and elaborate cameras, have become a spectacle rolling through the city’s roads since they began offering rides to passengers last year.

The question becomes, what exactly needs to be changed? To find out, the region only had to ask. In March, the Regional Transportation Alliance of Southwestern Pennsylvania released a comprehensive report titled Imagine Transportation 2.0 that describes seven guiding principles and 50 specific ideas to improve mobility throughout the 10-county southwestern Pennsylvania region. The report’s fundamental and specific proposed transportation improvements stem from feedback and suggestions from a broad cross section of more than 350 local businesses, organizations, and community groups. The report showed that, across the board, people want multi-modal means of transit, and they want to be able to move with efficiency.

Pittsburgh’s roadways thankfully don’t often experience the level of stagnation and congestion seen in cities like Los Angeles or Chicago. But that’s not to say Pittsburgh drivers enjoy a clutter-free commute every day. Drivers know that driving inbound or outbound of the downtown area during rush hour requires patience. Stretches of the Parkway East and Parkway West (or Interstate 376, the official title) and entrances to the city’s various tunnels, such as the Fort Pitt and Squirrel Hill Tunnels, regularly become backed up. Part of the problem lies not with the cluster of cars but with the area’s topography and geographical obstacles. The three rivers that define Pittsburgh’s landscape also limit the number of roadways and bridges into and out of the city. The gradient and volume of Pittsburgh’s myriad hills mean cars have to go through some of these hills via tunnels and that parallel routes can be hard to come by.

Instead of constructing sprawling new superhighways, the city can improve existing assets and infrastructure to diffuse the flow of highway traffic. Reconfiguring exit-only lanes can open the flow for once-restricted vehicles, as can adding new turn lanes and ramp configurations or otherwise modifying roadways to reduce traffic buildup. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation recently applied for a federal grant to cover part of a $200 million project to overhaul and reconfigure the Parkway West as it approaches and leaves the Fort Pitt Tunnel. It’s not a small project, but it’s an example of making efficient upgrades to existing infrastructure instead of building new channels.

In addition to reconfiguring roadways, technology can enable smoother traffic flow. Carnegie Mellon University’s computing, engineering, and innovation prowess has long benefited the Pittsburgh region and beyond. While CMU has been a trailblazer in autonomous vehicle development, it has accomplished even more in the transportation arena. Several years ago, researchers at the university unveiled technology enabling automated “smart” traffic-signal control. The technology uses sensors to automatically adjust and coordinate the red-light green-light rotation timing in traffic signals based on detected traffic volume. Upon installment at nine intersections in East Liberty, the smart devices reduced drivers’ wait time by 40 percent in some areas, speeding up travel time and cutting vehicle emissions by more than 20 percent.

Embedding smart traffic signal technology is cheaper in most instances than building new traffic lanes to control volume. But we’re far from seeing smart signals on every Pittsburgh street corner. Upgrading an entire traffic corridor can still cost in the millions, and only 1 percent of all traffic signals nationwide employ smart technology. Yet, as the Imagine Transportation 2.0 project demonstrates, there’s significant community interest in the technology, and it’s an area in which Pittsburgh could lead the way.

Aside from learning traffic patterns, smart traffic signal technology enables another key capability: communication with autonomous vehicles. With companies such as Uber, Argo AI, Delphi Automotive, and others, setting up shop or collaborating with organizations in Pittsburgh, the region is leading the development of driverless vehicles. CMU has been working on autonomous vehicle technology for 30 years, pioneering the very field. While the technology still has a long road to commercialization and ubiquity, there’s something magical in hailing one of Uber’s driverless cars for a ride around the city.

CMU, in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Department of Technology, has installed adaptive traffic signals throughout the region that can relay the signal phase to autonomous vehicles, essentially telling them when to stop and go. Such a system lays the groundwork for a vast network of signals that can communicate with an eventual fleet of autonomous vehicles, says Chris Hendrickson, PhD, an emeritus professor in CMU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and director of the university’s Traffic21 institute. “Having a city and county be receptive to new technology has really made a difference around Pittsburgh and will make a difference in the future,” he says. CMU’s flagship driverless vehicle—a modified Cadillac—made the 33-mile drive from Cranberry to the Pittsburgh International Airport in 2013, showcasing the technology’s capabilities.

Aside from increasing efficiency—autonomous vehicles can better maintain proper speed and more fluidly merge with other traffic, among other streamlined abilities—driverless automobiles stand to vastly improve safety and reduce traffic accidents, which Hendrickson says is their biggest benefit. This also means reduced traffic jams from automobile accidents, which Hendrickson says cause 20 percent of traffic congestion nationally.

Pittsburgh clearly isn’t short on ideas to improve the mobility of its population and launch new technologies. Doing so, however, requires funding and willingness to invest. And, it takes the right governmental and political will behind a project to make implementing ideas a tangible process. Former Pittsburgh mayor Tom Murphy Jr. pioneered this process, especially with bicycling. In the ’90s, bicycling hadn’t really caught on in Pittsburgh as a means of commuting. At a time when most bike transportation involved children biking to school, Murphy advocated for expanding Pittsburgh’s bike trails and boosting cycling’s popularity not only recreationally but as a viable and environmental mode of transportation.

Cyclists who now enjoy taking in the views from Pittsburgh’s riverfront trails and who revel in the ability to bike from Pittsburgh all the way to Washington, D.C., via connected bike trails, including the Great Allegheny Passage, owe something to Murphy’s vision.

Without Murphy’s advocacy, bicycling’s expansion in Pittsburgh, would have required some other, less-certain impetus. But the region has built on his momentum, and, in more recent years, Mayor Bill Peduto has pushed hard to install and expand bike traffic lanes throughout the region’s streets.

In 2014, bicycle-only traffic lanes sprung up on Penn Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Central Business District and along roads traversing Schenley Park between the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University campuses in Oakland. Saline Street in Greenfield was also one of the first streets outfitted with designated bike lanes.

While more bike lanes have been introduced throughout the region, their continued proliferation requires careful consideration. For the safety of cyclists, bicycle lanes must be strategically integrated with other bike-friendly streets and walkable areas. During their proposal period, some bike lanes, such as the downtown Fort Pitt Boulevard lanes, have drawn pushback from businesses and organizations that fear obstruction of customer parking and other interference. Earlier this year, the city proposed launching a bike lane advisory panel to ensure that as biking in Pittsburgh continues to grow, it does so with even more community input.

In 2015, the bike-share program Healthy Ride launched in Pittsburgh. After registering, program users can grab a bike from one of the 50 stations around the city, pedal off, and return the bicycle at any other station. It’s been a popular option for quick trips, lunchtime exercise, and short commutes. Bike stations can be found as far east as East Liberty and scattered about heading west into downtown. There are also stations across the rivers in the South Side and North Shore. At $2 for 30 minutes of ride time, Healthy Ride offers one of the most inexpensive bike-share programs in the country.

Late last year, the program received a $200,000 grant from the state’s Multimodal Transportation Fund to add 25 more stations throughout the area, the locations of which are being planned. Healthy Ride’s website contained a feature to allow community members to recommend new-station locations—it received hundreds of suggestions.

When a bike ride just isn’t feasible, it’s common to see bicyclists stow their bikes on the mounted racks affixed to the front of Port Authority’s buses. The Port Authority operates an expansive fleet of buses that traverse Allegheny County, plus the Pittsburgh Light Rail system, or the “T,” which spans 26 miles from the South Hills suburbs, through Downtown, and out to the North Shore, via an under-the-river tunnel. Port Authority has been moving Allegheny County for more than 50 years and remains widely used today. In 2016, it provided more than 62 million rides, taking the equivalent of 19,000 cars off the region’s roads. To maintain flexibility, the Port Authority compiles feedback from riders and community members each year before deciding on bus route changes and expansions.

Today, the Port Authority is on the verge of launching one of its most ambitious undertakings, the Bus Rapid Transit project. The BRT will better connect the Oakland neighborhood to Downtown Pittsburgh by implementing electrically powered express buses that use designated travel lanes. While these two areas are hubs for businesses and jobs, traveling the 2.6 miles from the center of Downtown to central Oakland can take 18–25 minutes on a regular Port Authority bus during rush-hour traffic—the BRT aims to shave this trip to 10 minutes.

“The project is very much alive and on track,” says Jim Ritchie, Port Authority communications officer. But the proposal aims to accomplish more than just faster transit. By introducing bus stations along the BRT travel lanes, the program should spur uptown development, an area between Oakland and Downtown with lots of potential for property growth. Fluid mobility between Oakland and Downtown will also breathe even more new development into these two key economic sectors.

While launching the BRT is estimated to cost $200–$240 million, federal grants could help with funding. The BRT also intends to extend beyond its Oakland-Downtown focus. Port Authority has been soliciting feedback on additional BRT routes and plans to expand the BRT’s service routes out to Squirrel Hill and Greenfield; to Highland Park; and via the East Busway to Wilkinsburg.

Yet not all transportation innovations involve transporting people. On the regional and national stage, transportation is a pillar of economic robustness and the free flow of goods. To this end, rail freight transport remains both vital to and active in Pittsburgh. Many of Pittsburgh’s railroads were built along its riverbanks, where trains could more easily negotiate the less hilly terrain. Even though the city has converted some riverside railroad sections into bike trails, Pittsburgh remains a crossroads between the Midwest and East Coast ports, making it a focal point for rail transport. With the Panama Canal’s recent expansion, more shipments will flow into Baltimore and other Atlantic port cities before being transported via rail through Pittsburgh en route to the West Coast and other areas between.

While the railroad industry has long been fastidious at maximizing efficiency, the railroad giant CSX Transportation Inc. is launching a $60 million intermodal facility in McKees Rocks. The Pittsburgh Intermodal Rail Terminal facility and railways will enable incoming shipping containers to be loaded onto trucks for delivery and for trucks to drop off shipping containers for rail transport. The center will boost efficiency and Western Pennsylvania’s connection to the global marketplace. Plus, railroads provide fuel-efficient, environmentally friendly means of shipping compared to truck transport, and more long-distance freight rail transport means fewer trucks making the long haul.

Similarly, Pittsburgh’s waterways still play a pivotal economic role, as they have throughout history. The convergence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers have put Pittsburgh at a “very strategic location” for the literal flow of goods and product, says Susie Shipley, president of Huntington Bank Western Pennsylvania and Ohio Valley Region and chair of the Port of Pittsburgh Commission. The Port of Pittsburgh Commission oversees recreational and economic development along 200 miles of southwestern Pennsylvania waterways spanning 12 counties.

These waterways enable barges and boats to ship everything from raw materials for mining and metals manufacturing to grains and agricultural goods, among other commodities. A single barge might carry 60–70 truckloads worth of product, Shipley says. Plus, waterway transport is more efficient, cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and safer than other means, she adds. Pittsburgh is the fourth-largest inland Port in the country, Shipley says, and the area’s waterways carried 28 million tons of cargo in 2015.

The Port of Pittsburgh Commission continues to actively promote the region’s waterways to ensure that companies considering business in Pittsburgh take advantage of its river highways. “In this region, you can source and manufacture almost anything,” Shipley says, “and by leveraging the intermodal system that we have here, including the waterways, you can get your product and distribute your product almost anywhere, quite frankly, in the world.” Of equal interest is the potential development of riverfront land sites for manufacturing facilities along the Monongahela and Ohio Rivers, which could leverage their advantageous river proximity. The Port of Pittsburgh is also currently working to maintain and improve its network of locks and dams along its waterways, which are vital for the smooth, safe passage of ships.

When people move to Pittsburgh, they want to know, will they be well-connected to the outside world? The short answer is yes—they’ll be perhaps better connected than ever. In only the past few years, Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) has achieved significant progress. In 2014, the airport served 37 nonstop flight destinations. As of 2017, it offers 68 nonstop destinations. “Personal time is money, and we understand that people don’t want to connect. We’re focused on providing that nonstop service to as many cities as possible for both our leisure and business travelers,” says Bob Kerlick, vice president of media relations at the Pittsburgh International Airport. After more than a decade of decline in total flyers, Pittsburgh’s airport has seen three straight years of increasing passenger volume, Kerlick says.

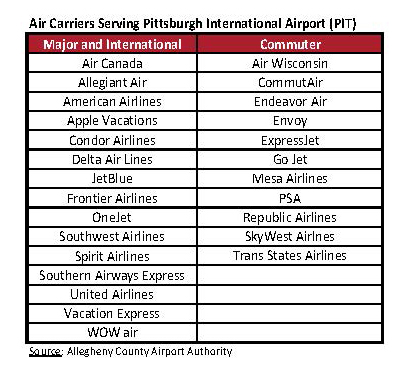

In 2015, Christina Cassotis became the Allegheny County Airport Authority CEO, bringing new excitement and aggressive air service expansion plans. PIT has added three new airlines in 2017: Spirit Airlines, Condor Airlines, and WOW air. The addition of these three low-cost flight providers increases options and the range of destinations for passengers.

WOW air offers nonstop flights to Reykjavik, Iceland, with the idea that passengers can fly from Pittsburgh to Iceland and then connect to more than 20 Europe destinations nonstop. Condor Airlines flies directly from Pittsburgh to Frankfurt, Germany, providing PIT’s first nonstop service to Frankfurt since 2004. PIT also offers air charter service to China as of 2017.

Domestically, one of PIT’s current goals is to expand and improve connectivity to the West Coast for in-demand areas such as Seattle and the San Francisco Bay Area. Southwest Airlines, which provides the highest number of direct flights from Pittsburgh’s airport, recently added Los Angeles to its list of nonstop destinations. Last year, PIT was also one of the first airports in the country to permit ridesharing providers Uber and Lyft to pick up and drop off airport passengers.

Given its recent headway, Pittsburgh’s airport stands well-poised to continue its upward trajectory. But the airport isn’t alone in this position. Transportation in Pittsburgh, whether by car, bus, bike, or other means, can sustain and build on its advances. Recent innovations and progress benchmarks have laid the path for the Pittsburgh region to not only make its population more mobile but to shape the future of mobility itself. Such change takes time, but the key components are already in place.

What will not change is the correlation between improved mobility and stronger regional and economic development. Simply put, people who can move around can get things done. As Ken Zapinski of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development says, transportation will always remain a critical tool for success.

“At the end of the day transportation is not an end in itself. It’s just a tool. It’s a tool to build attractive communities. It’s a tool to help connect people to opportunities. And it’s a tool to attract business investment, all of which feed on each other.” mg